AUCKLAND, NEW ZEALAND—As he paints, David Owain Jones sometimes feels he’s trying to figure out exactly why he is so fascinated with figurative and representational painting. And why he’s so driven to paint year after year. Once he’s resolved that enigma, maybe he’ll stop painting, he laughs. Whether he’s joking is hard to tell.

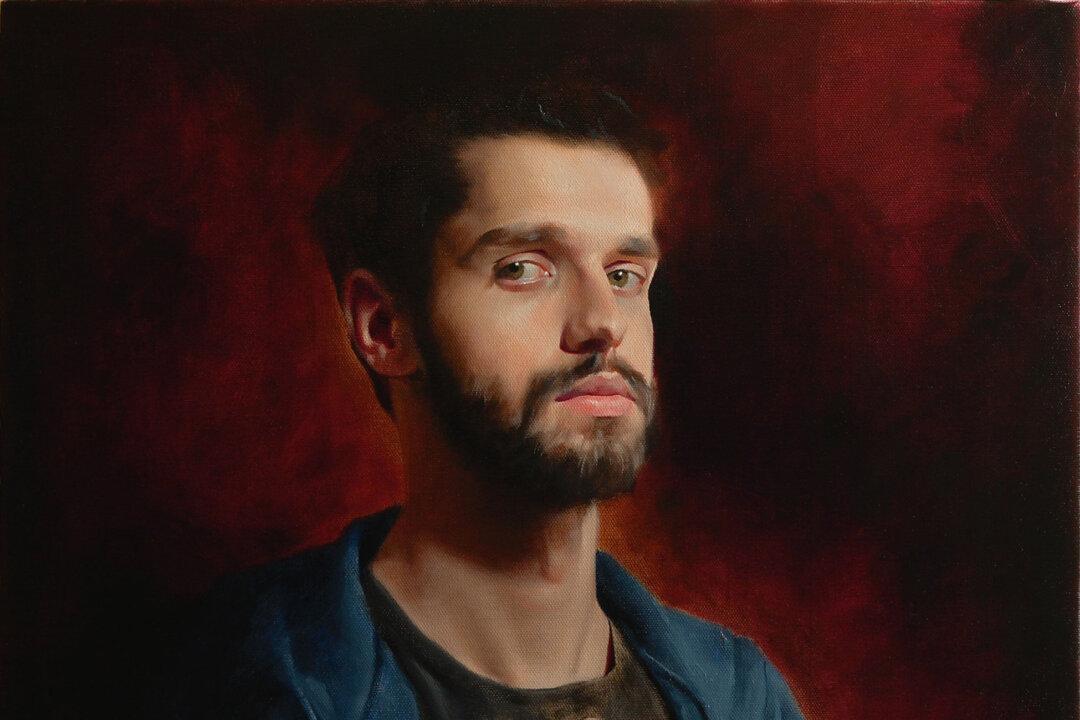

David Owain Jones in his studio in Auckland, New Zealand, on March 28, 2019. Lorraine Ferrier/The Epoch Times