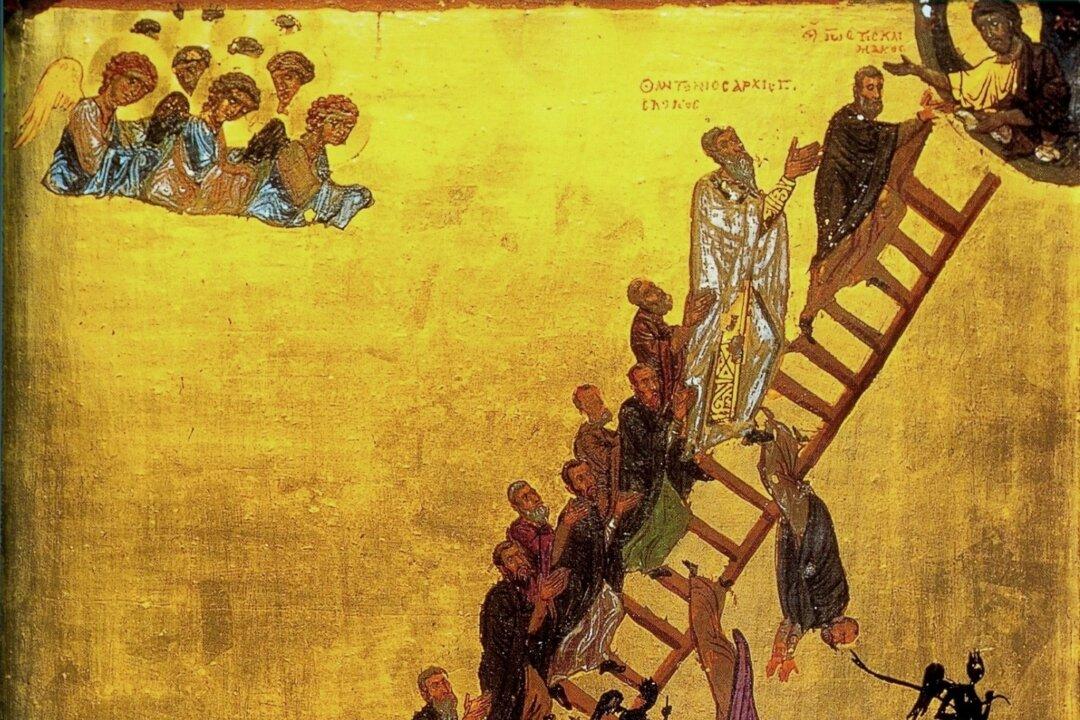

For centuries, Byzantine art acted like a compass, orienting the devout in their faith and, ultimately, guiding them to their salvation. The Byzantine artist painted in a specific style, a visual language if you like, that Orthodox Christians understood. “His role was akin to that of the priesthood and the exercise of his talent a kind of liturgy—liturgy in a sense almost sacramental—rather than a didactic function,” as stated in “The Oxford Companion to Art.”

Every part of Byzantine art brings the devout closer to God. “The arrangement of mosaics or paintings in a church, the choice of subjects, even the attitudes and expressions of the characters, were all determined according to a traditional scheme charged with theological meaning.”