PONTASSIEVE, Italy—Passion and perseverance are at the heart of the Bianco Bianchi workshop in the little town of Pontassieve, a short train ride from Florence. Bianchi (1920–2006) always had a passion for painting, and it was through his love of art that he dedicated his life to learning about and restoring the lost art of scagliola.

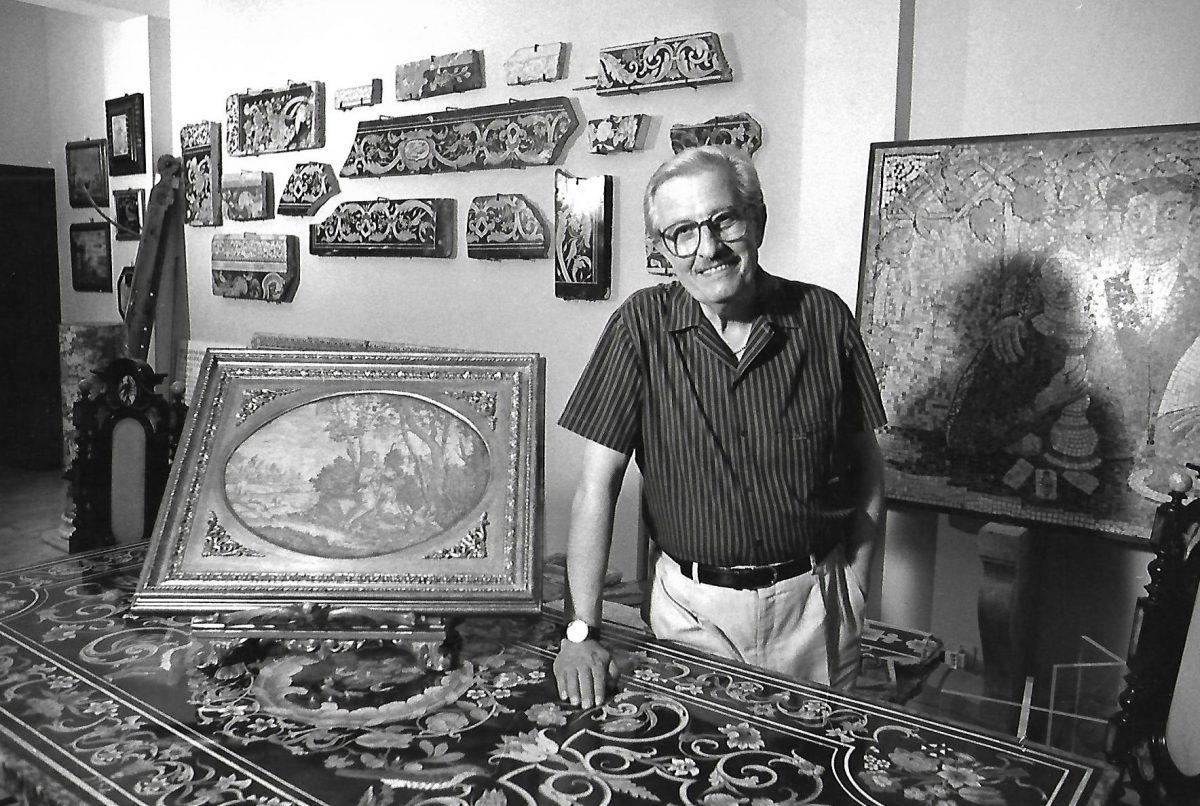

Bianco Bianchi (1920–2006) established his scagliola workshop in 1953 and dedicated his life to preserving the art. Bianco Bianchi