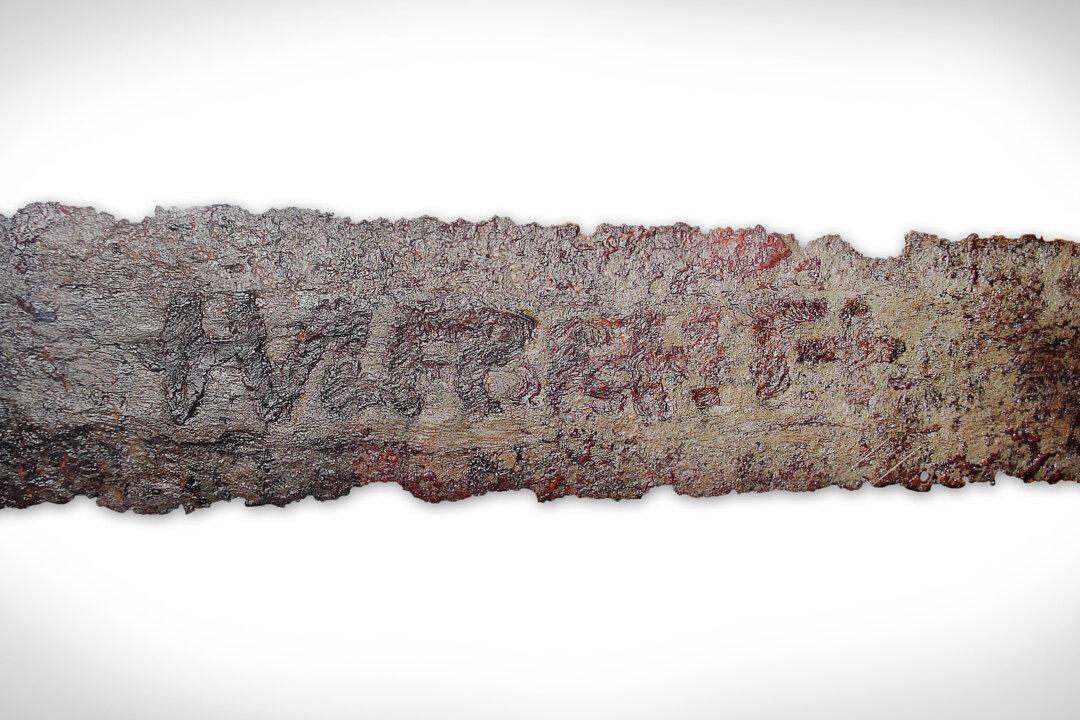

The famed Ulfberht Viking swords were made of metal so pure it baffled archaeologists. It was thought the technology to forge such metal was not invented for another 800 or more years, during the Industrial Revolution.

About 170 Ulfberhts have been found, dating from A.D. 800 to 1,000. A Nova National Geographic documentary titled “Secrets of the Viking Sword,” first aired in 2012, took a look at the enigmatic sword’s metallurgic composition.