A little more than a century ago, education in America followed a very different vision than it does today.

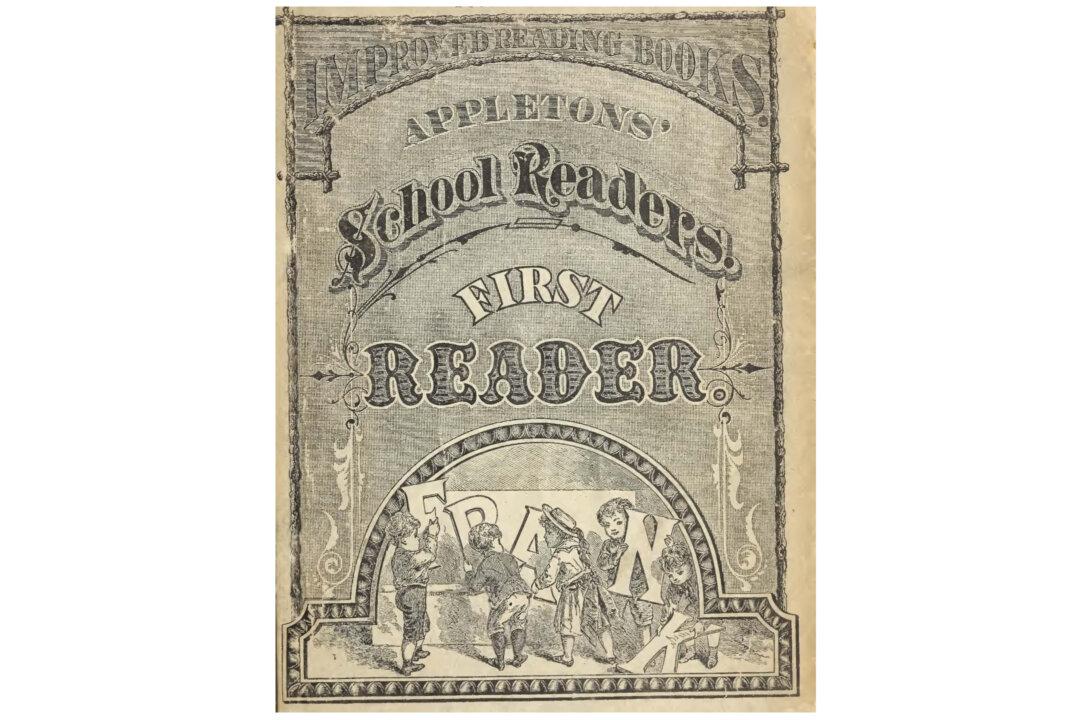

A few years back, I encountered a vintage relic in a used bookstore that, for a mere $6, opened my eyes to how much we have lost. “Appletons’ Fifth Reader” is the last volume in a 19th-century textbook series that emphasizes tradition, patriotism, and good taste.