(The Parthenon uplifted on its rock first challenging the view on the approach to Athens.)

Abrupt the supernatural Cross, Vivid in startled air, Smote the Emperor Constantine And turned his soul’s allegiance there. With other power appealing down, Trophy of Adam’s best! If cynic minds you scarce convert, You try them, shake them, or molest.

Diogenes, that honest heart, Lived ere your date began; Thee had he seen, he might have swerved In mood nor barked so much at Man.

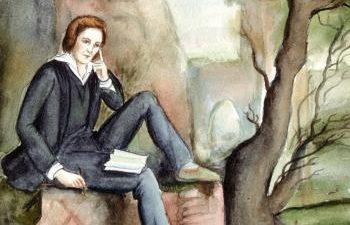

Have you ever undergone a conversion experience? One where, in a sudden flash, you fundamentally changed your perspective? Such moments, which define our lives, are not easily forgotten.In the first stanza of this poem, Herman Melville describes the conversion experience of the Roman Emperor Constantine. It is said that before a crucial battle he looked up to the sun and saw a cross of light above it. When victory came, he declared that his empire convert to Christianity, even though it had once burned Christians alive.