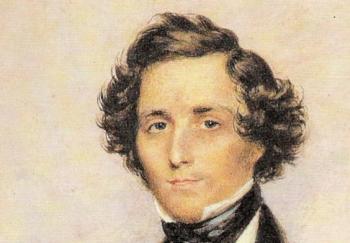

We are approaching the last month to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the birth of Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy.

Throughout the year, especially in Leipzig, the center of his life and musical work, Mendelssohn has been celebrated with concerts. Musicians like the world-renowned violinist Anne Sophie Mutter contributed to the celebration; Mutter, on this occasion, re-recorded Mendelssohn’s violin concertos.

Living a charmed life, as his name predicted (Felix means “the happy one” or “the fortunate one” in Latin), Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809-1847), was one of the most extraordinary composers of the 19th century. His relatively short life—he died at 38—had many similarities to Mozart´s, not the least of which, due to his industriousness, was his great influence.

Mendelssohn’s musical education followed the strict rules of the Classical period while his talent and personality unfolded in the early Romantic era. Thus, his work is unmatched in drawing on the qualities of both.

Unlike his contemporaries Schubert and Schumann, whose works display the dark and melancholic mood commonly associated with the Romantics, Mendelssohn´s music breathed joy, serenity and elegance. At the same time it was emotional and inclined to narrative.

His oratorios, majestic and splendid monuments of faith, became fundamental works of the 19th century musica sacra and prove that he also was capable of great depth and profound musical language.

A Child Prodigy

Although Felix’s father, Abraham Mendelssohn, was the son of the Jewish philosopher Moses Mendelssohn who reformed the Judaism of the 18th century, Abraham baptized and raised his children as Protestants. An avid enthusiast for the arts himself, Abraham soon recognized the great talent of his children.

The children had more than a musical bond; the emotional tie between the siblings, Fanny and Felix, was strong and lasted throughout their lives.As the family was well-situated, Fanny and Felix were educated by the best teachers, intellectuals, and musicians. Among them was Carl Friedrich Zelter, who earned a great reputation as a music professor and composer.

Mendelssohn, then, had the best conditions to grow up as a prodigy. In 1818, at the age of 9, he appeared for the first time in public. The next year he joined the choir Berliner Sing Akademie which Carl Friedrich Zelter directed. Here Mendelssohn started to study the music of the masters.

At the age of 11, he started composing, completing 60 pieces his first year, including songs, piano sonatas, piano trios, and a sonata for violin and piano.

During the Biedermeier era, it was common to host music soirees every Sunday afternoon at home. Felix used this opportunity to conduct an amateur orchestra that, from 1822 on, was supported by the professional musicians of the Berlin Court Chapel. He composed the music for these occasions and practiced them at home.

At 17 he wrote his masterpiece, “Overture to ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’ “ which was later completed for Shakespeare’s play with other pieces, including a Scherzo, Nocturno, and Wedding March.

Mendelssohn had an amazing ability to memorize music. Once, when he accidentally left a score in a carriage, he was able to simply rewrite the lost music from memory.

At 20, he accomplished an historic coup in the world of music: He uncovered forgotten parts of Johann Sebastian Bach’s “St. Matthew Passion“ in Leipzig and determined to perform it as a whole. This oratorio had only been performed in parts at the time. Against the wishes of his teacher Zelter, he brought late honor to Bach´s masterpiece which, in fact, led to a renewed appreciation of Bach at the time.

Later in life, Felix Mendelssohn stayed in contact with some of the most influential personalities of his time—the German genius Goethe was one of his many friends.