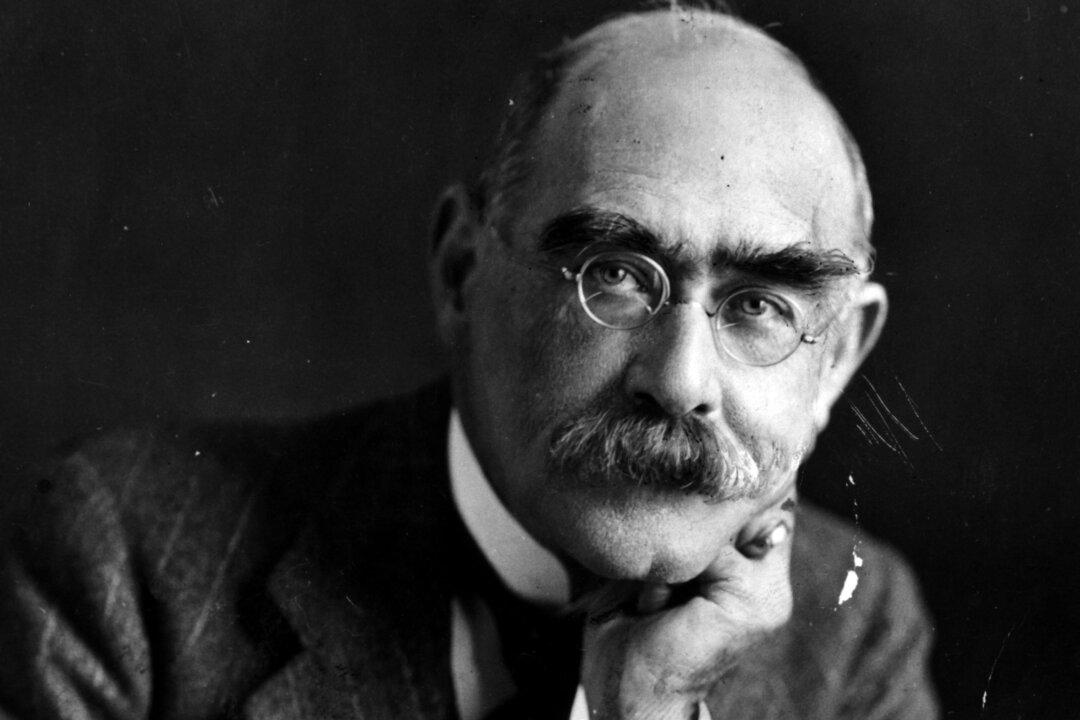

Rudyard Kipling’s “The Gods of the Copybook Headings” was published in London in 1919, and in the United States in Harper’s Magazine in January 1920—just over 100 years ago—as “The Gods of the Copybook Margins.” It is sometimes referred to as “Maxims of the Marketplace.”

Copybooks in Kipling’s day—in the UK and, perhaps, in the United States—were books with lined pages, similar to a “yellow pad” today, but at the top were short sayings: aphorisms, maxims, verses from Scripture that drilled into the young student’s perception the rules for life, the things that mattered, ostensibly given not as moral instruction but as examples for penmanship. On the dozen lines beneath, the student, using cursive script, wrote an exact copy, one copy on each line, until he had written the same maxim a dozen times—technically, to learn the art of exact handwriting, but in fact to have certain ideas driven into his or her head.