“Like one that on a lonesome road”

Like one that on a lonesome road

Doth walk in fear and dread,

And having once turned round walks on,

And turns no more his head;

Because he knows, a frightful fiend

Doth close behind him tread.

— Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772–1834)

That faint, uneasy prickle on the neck. That sense of being watched. That sudden raising of gooseflesh. It’s a moment that both terrifies and fascinates us. It takes us beyond the here and now—enlarging our understanding of ourselves—but what if we get caught forever? What if we can never return to normality?

Poetry is the best vehicle for this kind of imaginative experience, granting us both the power to open the doors of perception—and to close them with a turn of the page. The great Romantic writers, in particular, wrote narrative poems that take us into strange worlds of enchanted sounds and images: Keats’s “La Belle Dame Sans Merci,” for instance, or Shelley’s “Alastor” and Tennyson’s “The Lady of Shalot.”

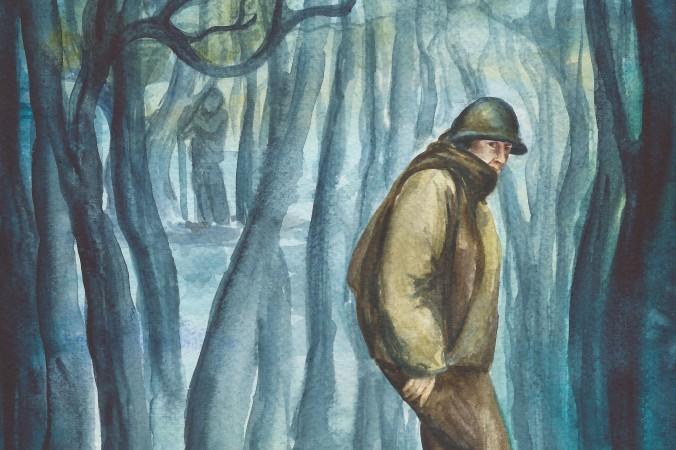

“The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” is perhaps the most famous of all Romantic journeys. As we recite it, we become one with the mariner, who for the mere act of shooting an albatross is plunged into a living nightmare.

Together, with the mariner, we see the sun swallowed up by the ocean. We see the skeleton of a ship on which a vampiric woman and death play dice. We see a million, million slimy things in the deepness of the waves. Worst of all, the sailors around the mariner all drop dead.

This extract describes the mariner’s feelings towards the end of his trial. The offered simile of the lonely traveler is so vivid and so universal that it could almost be a poem in itself—and often becomes so when quoted out of context, in innumerable books, films, and television programs. I first heard of it, for example, not from any prim and proper poetry anthology, but from a “Doctor Who” novelization, which begins with a backpacker being hunted through the spooky woods by an evil alien slug.

Who can’t identify with the image of the traveler on the “lonesome road?” It speaks to that experience that we have all had of being alone and being overwhelmed with a sense of vague, growing anxiety. Our imagination takes over and we begin to fantasize that all sorts of horrors are stretching their fingers toward us.

This passage works on many different levels, including the psychological and the existential. If we have ever been scarred by a bad event are we then condemned to live in its shadow, afraid of it reoccurring? Is the “frightful fiend” not a ghost or a ghoul, or anything fantastical, but in fact the reality of death we cannot escape? When we say these words aloud, we feel the heavy, almost mechanical beat of the traveler’s footsteps, as he wills himself to keep going despite his fear. There is a slow, doom-laden music that swells in the final line to a shiver of pure dread.

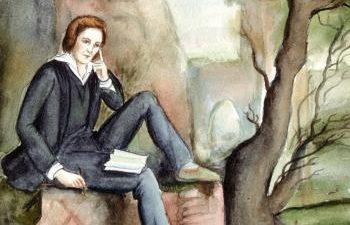

Is it odd or disturbing to read of such dark emotions? When I was studying at a university, I knew a fellow student who, whenever she was feeling depressed, would draw the curtains and recite Coleridge’s classic from start to finish. There is, indeed, something curiously healing about the mariner’s encounter with suffering at its most extreme. We live through his trauma to emerge somehow cleansed and new.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772–1834) was an English poet, literary critic, and philosopher.

Christopher Nield is a poet living in London.