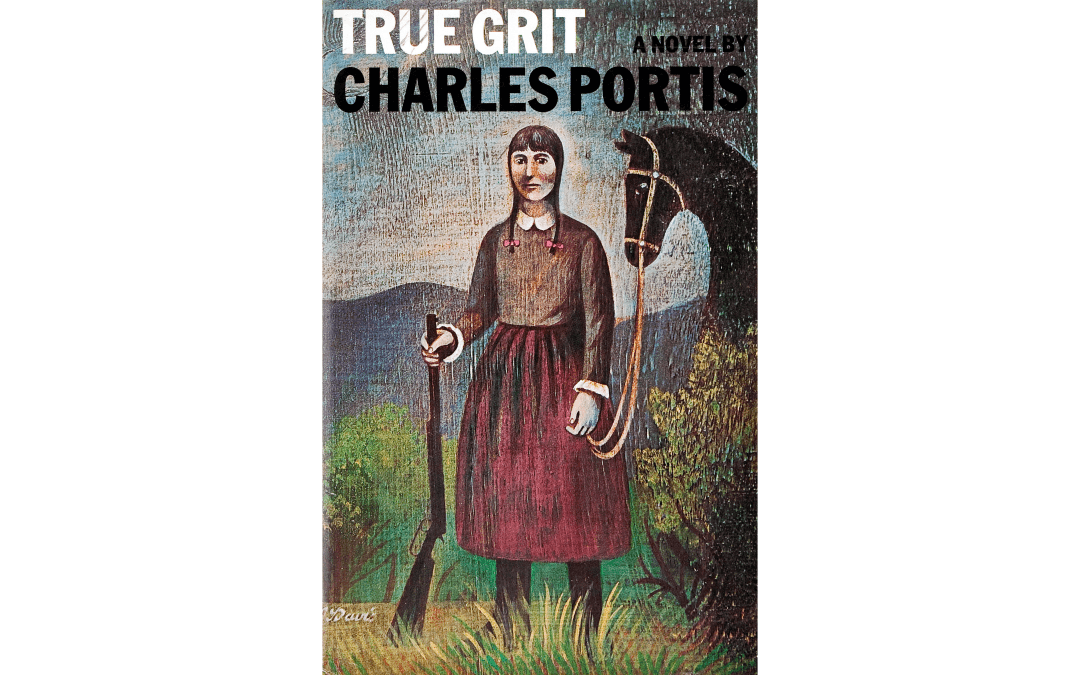

No one trifles with 14-year-old Mattie Ross.

When hired hand Tom Chaney murders Mattie’s father in cold blood and steals his horse and hard-earned cash, it’s Mattie who sets out to retrieve her father’s body and to track Chaney to the ends of the earth, if need be, and either kill him or bring him to justice. She’s accompanied on the first stage of this journey by a neighbor, the kindhearted Yarnell.