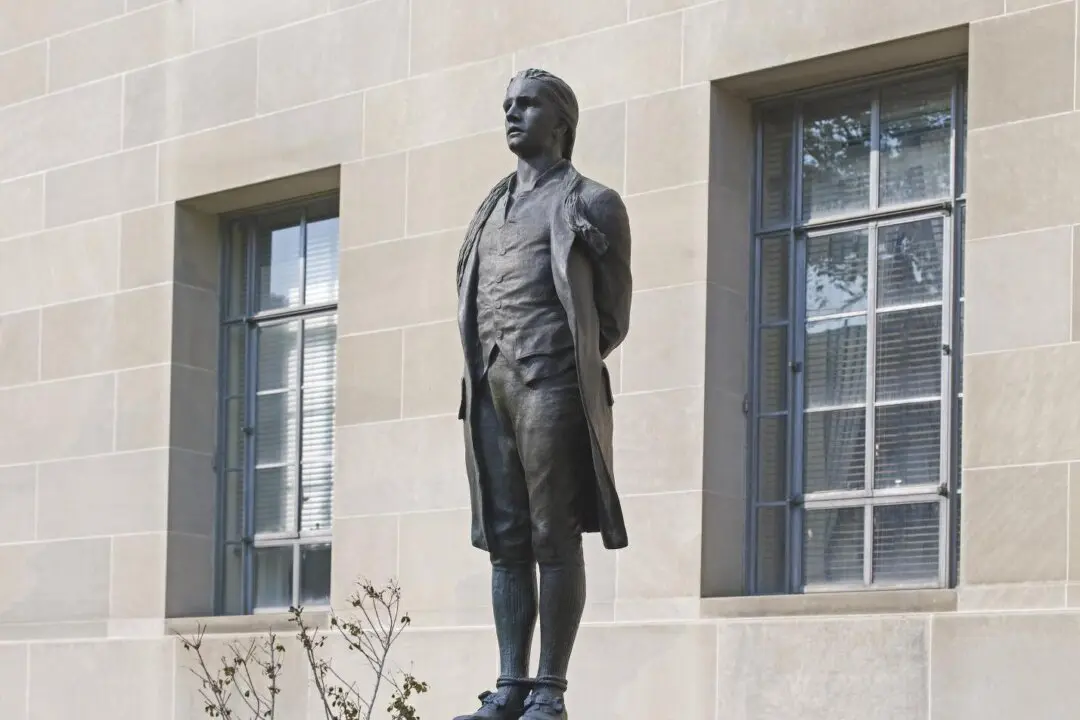

George Washington—surveyor, farmer, soldier, and statesman—never thought of himself as an economist, but experience taught him a great deal about fiat (unbacked) paper money. When the Congress foisted it on his Continental Army and tried to pay for food with it, his men suffered privation.

By contrast, the nearby British ate well because they paid in gold and silver. A few years later, in 1787, Washington declared that the inevitable effects of paper money were “to ruin commerce, oppress the honest, and open the door to every species of fraud and injustice.”