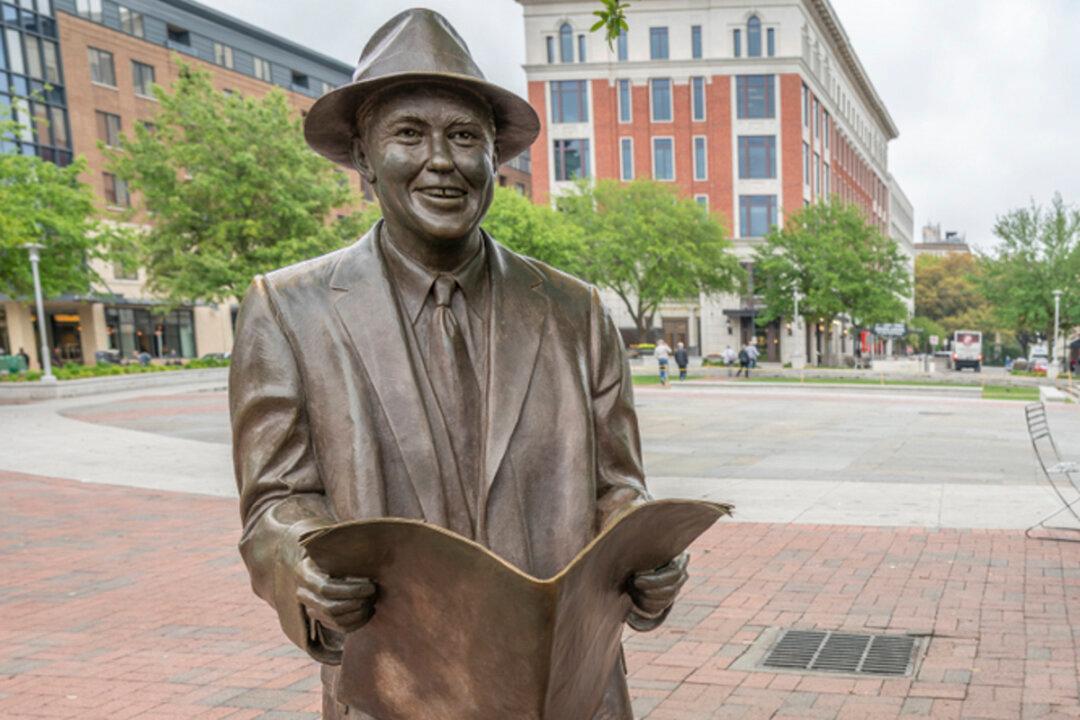

His words inhabit the psyche like a soundtrack of the American century, from the autumn leaves falling past my window to the Atchison, Topeka, and the Santa Fe. Johnny Mercer (1909–1976) was America’s lyricist, giving voice to the loves, ambitions, hopes, dreams, and whimsies of his country’s people for four decades.

A slim sampling of Mercer’s 1,500-plus song lyrics is a virtual history of the American popular song from the 1930s through the 1960s: “Lazy Bones,” “Hooray for Hollywood,” “Jeepers Creepers,” “You Must Have Been a Beautiful Baby,” “That Old Black Magic,” “One for My Baby (and One More for the Road),” “Ac-Cent-Tchu-Ate the Positive,” “Laura,” “Autumn Leaves,” “Glow Worm,” “In the Cool, Cool, Cool of the Evening,” “Satin Doll,” “Moon River,” and “Summer Wind.”