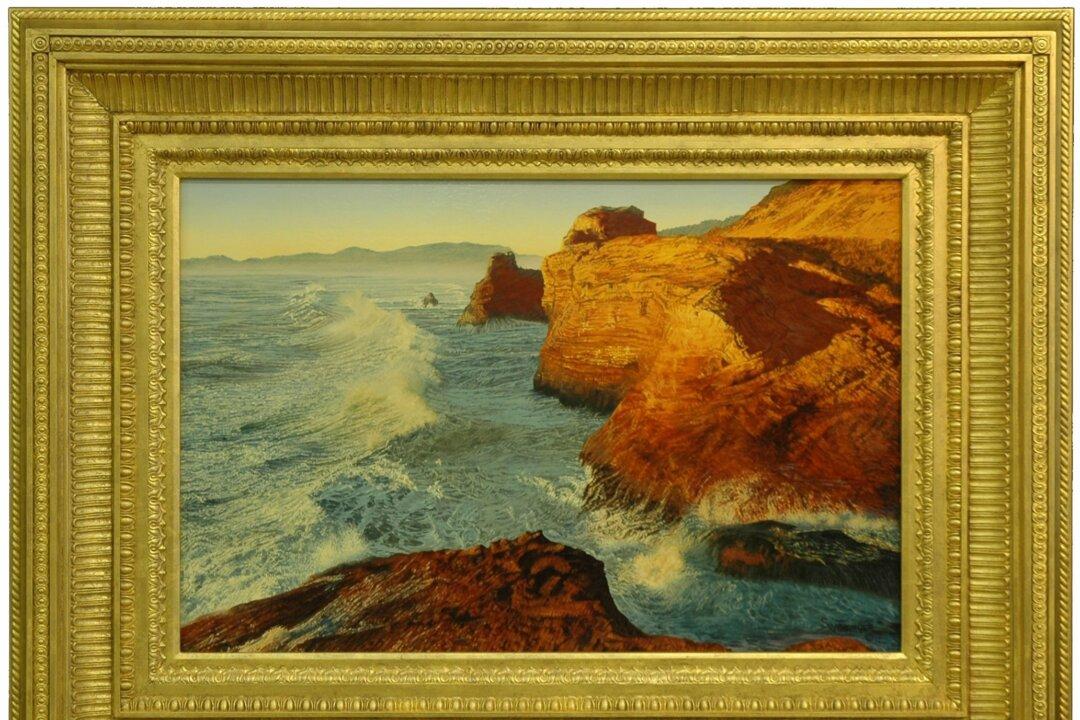

You won’t find American realist artist Steve Wineinger’s paintings online easily, if at all, but for decades he has been quietly painting and mastering his art on his farm near Spokane, Washington.

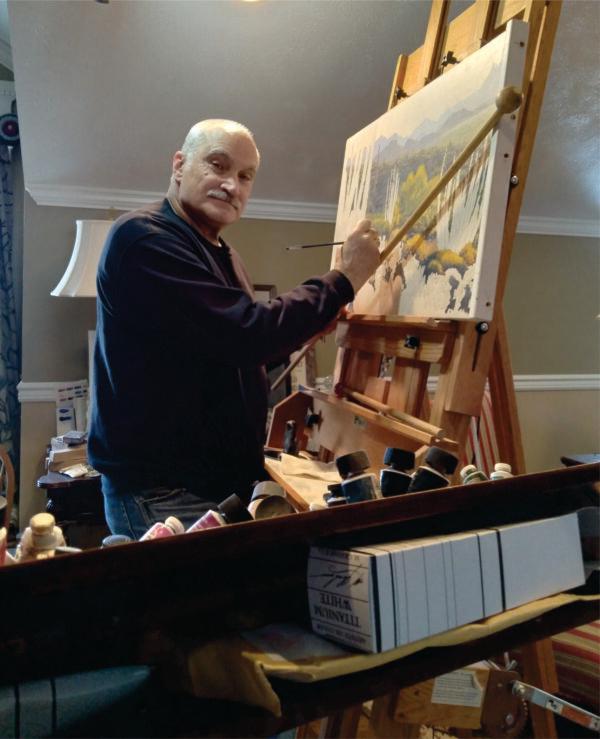

Realist painter Steve Wineinger in his studio in Spokane, Washington. Steve Wineinger