It is the night of December 25, 1776, and ice fills the Delaware River. The men of the Continental Army shiver as they cross under cover of night, on their way to engage Hessian troops at Trenton, New Jersey. Standing in the boat is a resolute George Washington, face steeled for the battle to come. Before the men boarded the boats, Washington had officers read to his soldiers the words from Thomas Paine’s “The American Crisis,” written only days before on December 23, 1776. The opening paragraph of the pamphlet reads,

“These are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands by it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly: it is dearness only that gives every thing its value. Heaven knows how to put a proper price upon its goods; and it would be strange indeed if so celestial an article as Freedom should not be highly rated.”Painted in 1851 by Emanuel Leutze, “Washington Crossing the Delaware” immortalizes the image of the ragtag Continental Army going forth from Valley Forge to engage the forces of the then greatest nation in the world. It is, rightly so, one of the most often reproduced images from American history. Open any good textbook on the subject, and it is there. Leutze’s portrait of Washington still evokes wonder today.

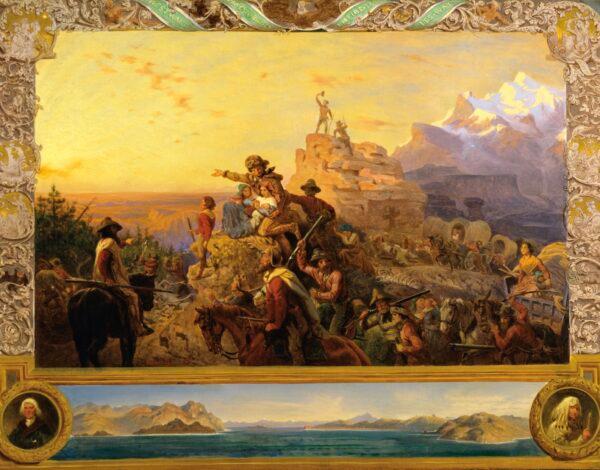

Painting study for “Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way” by Emanuel Leutze, 1861. Oil on canvas. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C. Public domain