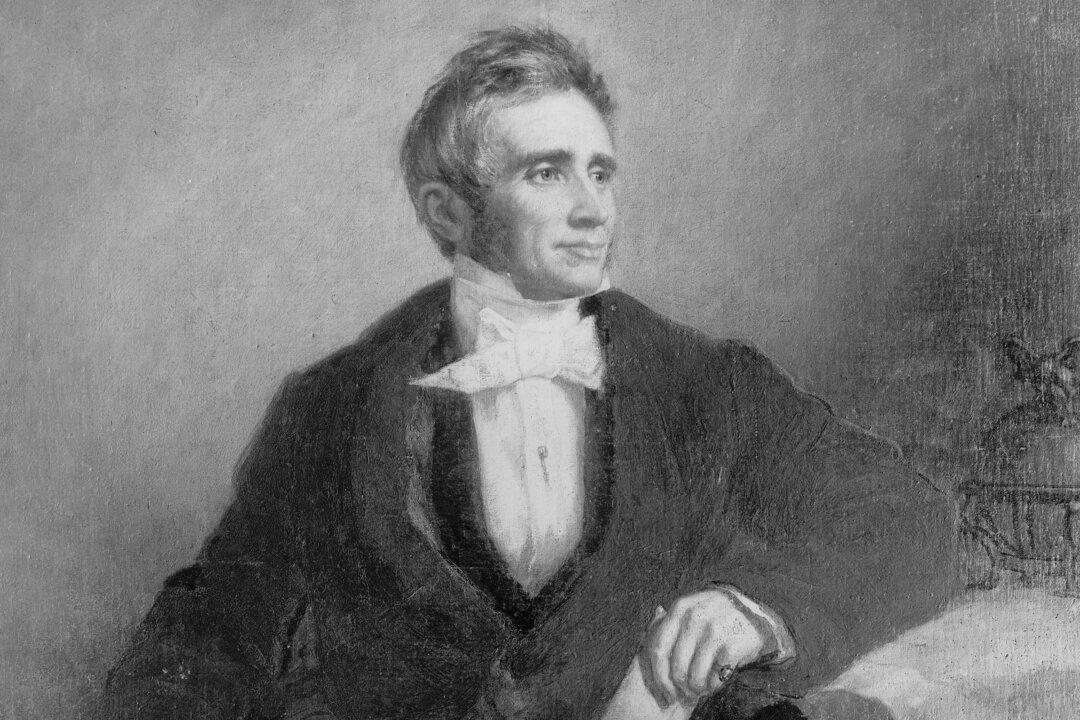

Amedeo Obici founded a nationwide business and industrial empire on the peanut, making the origins of the Planters Peanut Company a narrative forever tied to one great immigrant’s destination and destiny, struggle and hope, passion and perseverance.

Before he was a teenager, his weary shipboard voyage across the Atlantic carried him to New York City. The fatherless boy had been sent to visit an uncle and after a two- or three-week ocean passage from Europe, he touched land in America. Unaccompanied, unknown, and ignorant of its alien language and way of life, he had a handwritten note fastened to his clothing, specifying where and to whom he was to go.