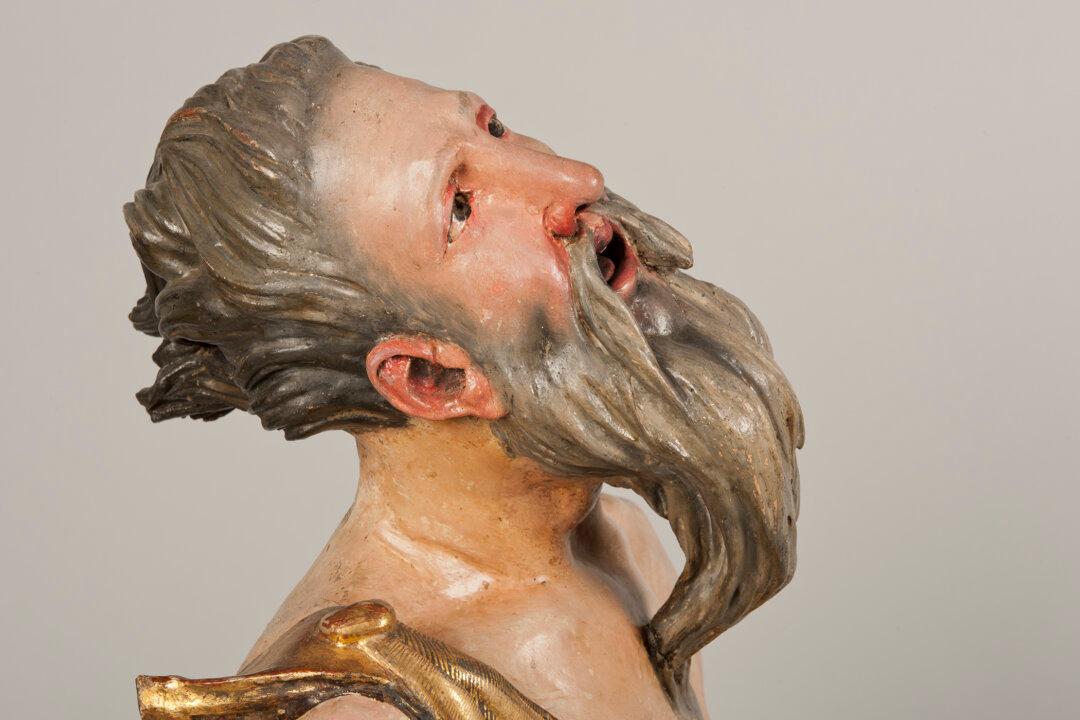

St. Christopher stares directly at me, and in a heartbeat I feel what he feels—even my mouth mirrors his. This realization, and level of intimate communion, makes me feel more than a little self-conscious as my gaping mouth brings me sharply back to reality. So palpable is St. Christopher’s conviction as he carries the Christ child on his shoulders across a river that I forget this St. Christopher is a polychromed wooden figure carved by Spanish Renaissance sculptor Alonso Berruguete.

Detail of "St. Christopher," 1526–1533, by Alonso Berruguete. Polychromed wood with gilding. National Museum of Sculpture, Valladolid, Spain. Javier Muñoz and Paz Pastor/National Museum of Sculpture, Valladolid, Spain