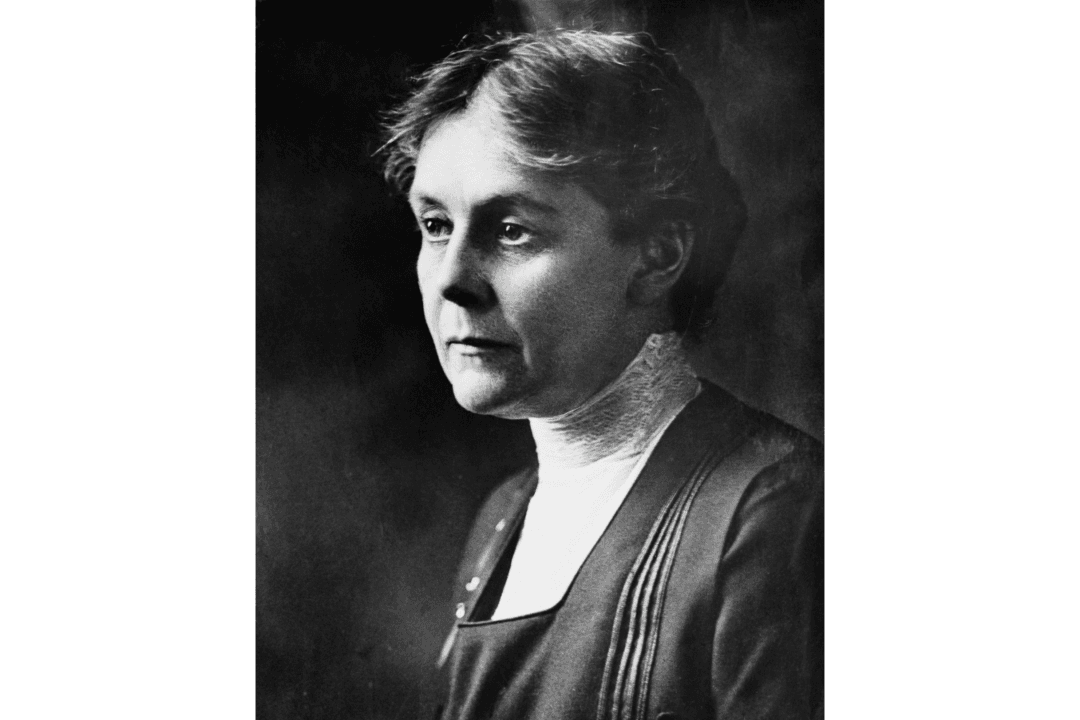

From a young age, Alice Hamilton (1869–1970) dreamed of making the world a better place. As a young lady, she held true to her Christian faith and dreamed of becoming a missionary. She chose to study medicine so that she could help others everywhere she went.

Finding Her Way

Hamilton was born in New York in 1869 and raised in Fort Wayne, Indiana, where she was homeschooled by her well-to-do family. At 17, she attended Miss Porter’s Finishing School for Young Ladies in Farmington, Connecticut for two years.Returning to Indiana, Hamilton studied at the Fort Wayne College of Medicine, then attended the University of Michigan Medical School in 1892. When she graduated, she worked at hospitals to gain clinical experience. However, she decided that starting her own practice was not her true passion.