Alexander Hamilton was born a bastard and grew up an orphan. Some might say that he didn’t get a fair shake at the start. He was born in Nevis, a very small island that was part of the British West Indies. He was born on Jan. 11, 1755. Or 1757. There isn’t an official record of his birth. His father, James Hamilton, had left the family early in his childhood, and only a few years before his mother, Rachel Faucette, died.

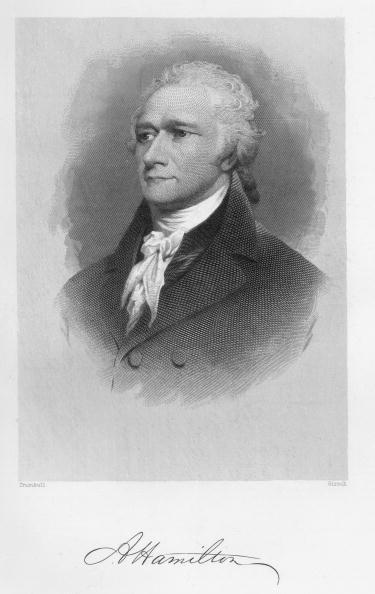

Alexander Hamilton, circa 1785. Engraving by Girsch. Hulton Archive/Getty Images