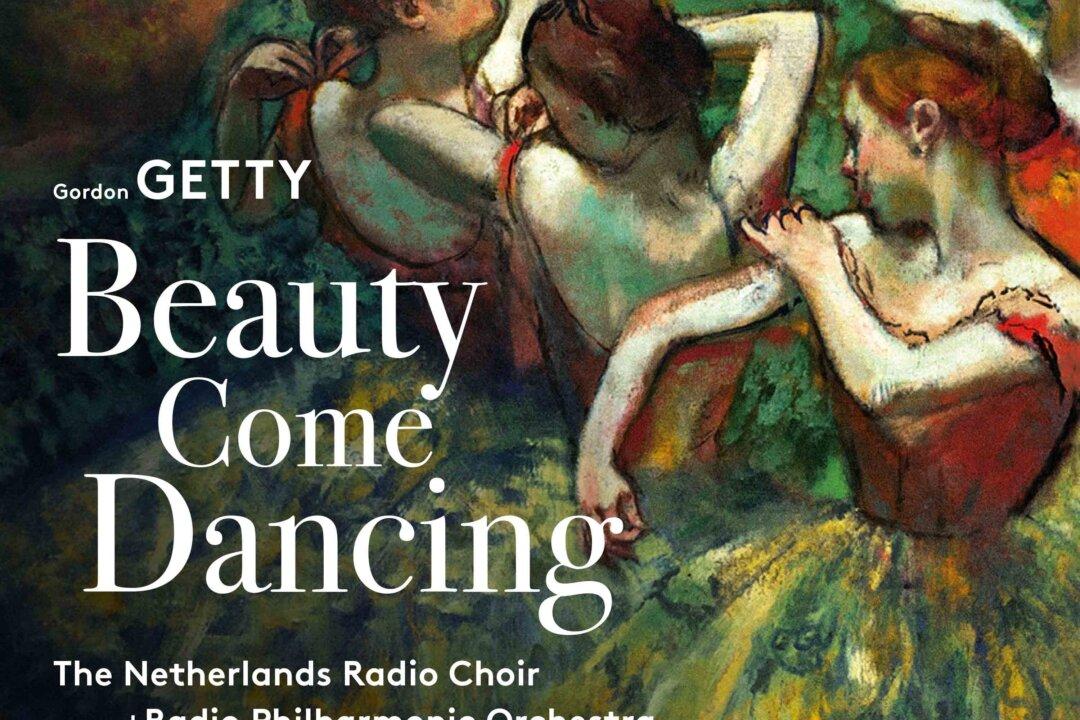

Gordon Getty (b. 1933) is a distinguished composer of songs and operas inspired by poetry. “Beauty Come Dancing” is a new release on the Pentatone label of Getty’s choral works performed by The Netherlands Radio Choir led by chorus master Klaas Stok, and The Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by James Gaffigan. This is the third album of his choral works.

Getty is a self-described conservative, both in the poetry that inspires him and the music he writes.