King Leonidas looked out upon the glinting mass of Persians winding up the valley toward him like the enameled back of a snake. He could hear the distant rumble of clanging armor and shouting men as the Persians advanced like the thundering sea that shimmered nearby. The restrictions of terrain prevented the enemy from casting its full weight and immense force against Leonidas and his Greek hoplites. Instead, the Persians squeezed their force into the mountain pass where they were confronted by Leonidas’ smaller army, which stood like an immovable wall. Despite the advantageous terrain, Leonidas knew how tenuous their position was. To his gaze, the enemy force appeared endless.

The Legend of Leonidas

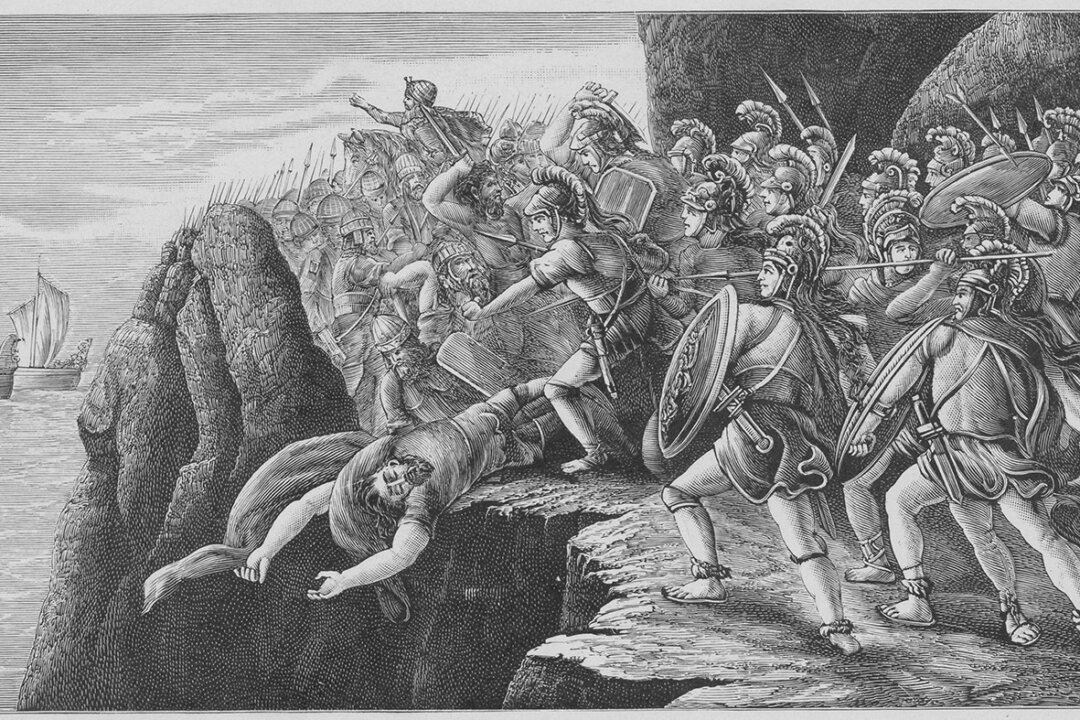

Textile of “Leonidas at Thermopylae,” circa 1815, after the painting by Jacques-Louis David. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Smithsonian Institution. Public Domain