NOTICE

Persons attempting to find a motive in the narrative will be prosecuted; persons attempting to find a moral in it will be banished; persons attempting to find a plot in it will be shot.

BY ORDER OF THE AUTHOR

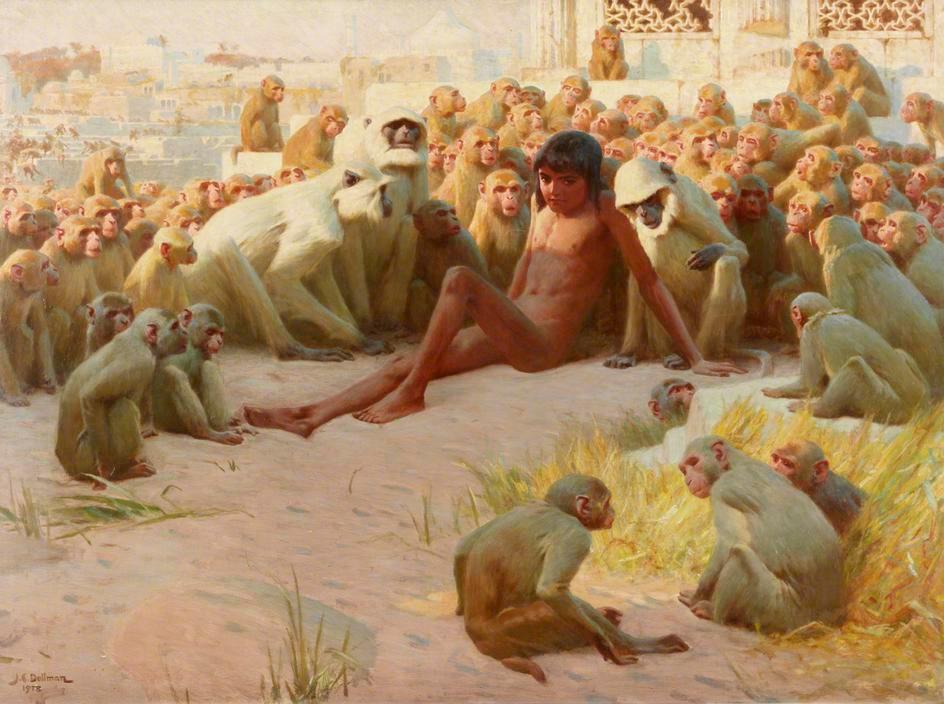

This warning famously graces the opening page of Mark Twain’s “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” setting readers up for a narrative of gritty humor and grinning irony. Since Mr. Twain did not order readers away from attempting to find a theme, we propose that though this American epic is full of pariahs, vagabonds, and rapscallions, it is also a story about kings.In the whole catalog of conjured heroes from Homer to Hemingway, not one is quite as kingly as Huckleberry Finn. And there never was such a king, either. Huck has royal poise, a regal demeanor, as he presides in straightforward fashion over his empire of mud and water.