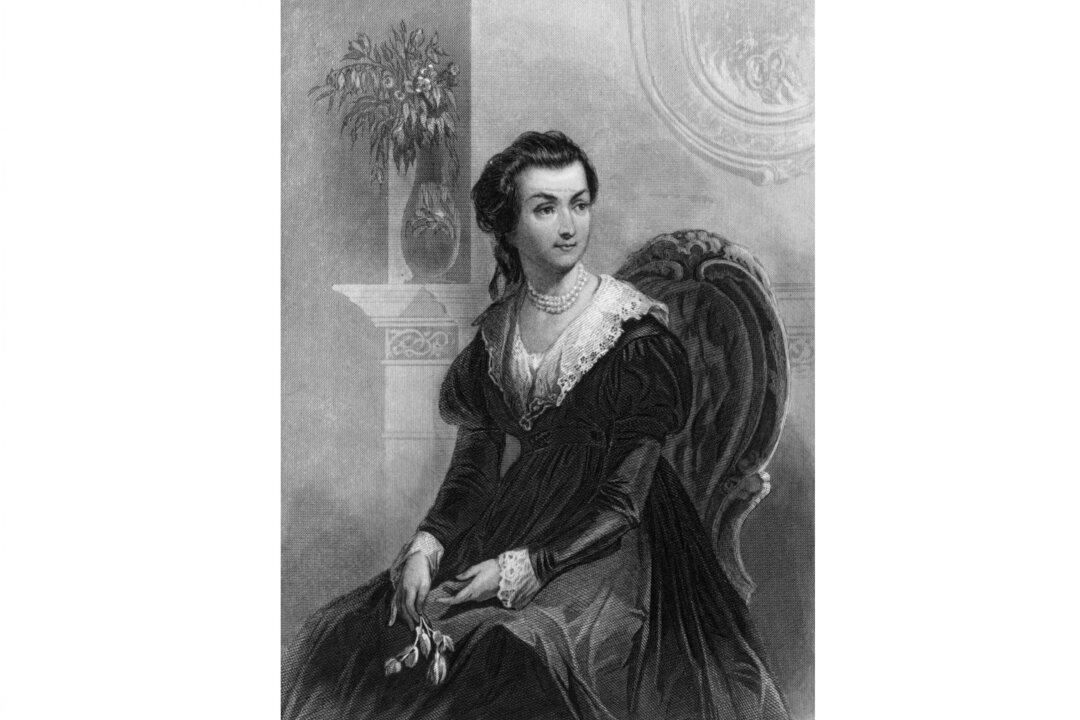

Abigail Adams was an amazing woman. No—that compliment cuts in half her talents and her ardor. She was an amazing human being.

“Faced with the unfamiliar task of providing financially for her children while her husband was in Europe for four years, Abigail used her imagination and discovered talents she hadn’t realized she possessed to accomplish her goal,” Natalie S. Bober wrote in the “Foreword” to her 1995 biography of this heroine.