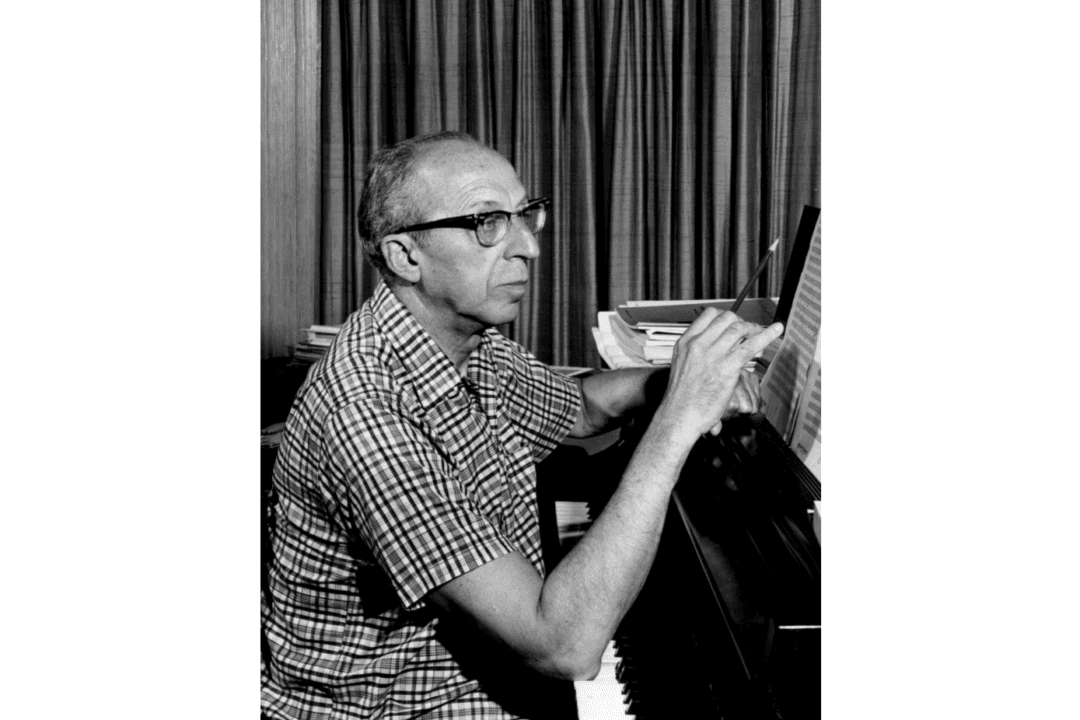

Nov. 14 is the birthday of the “Dean of American Composers.” Along with George Gershwin and Leonard Bernstein, Aaron Copland is considered one of our “big three” composers, among the very best our country has produced. And while people will always debate who exactly the best among them is, Copland produced more popular classical works than either of the other two (if one discounts Gershwin the songwriter and only considers his instrumental works, which often strayed into cacophonous jazz pieces).

So, in celebration of Copland’s birthday, here is a list of eight compositions that contributed to his reputation as a “populist” composer.