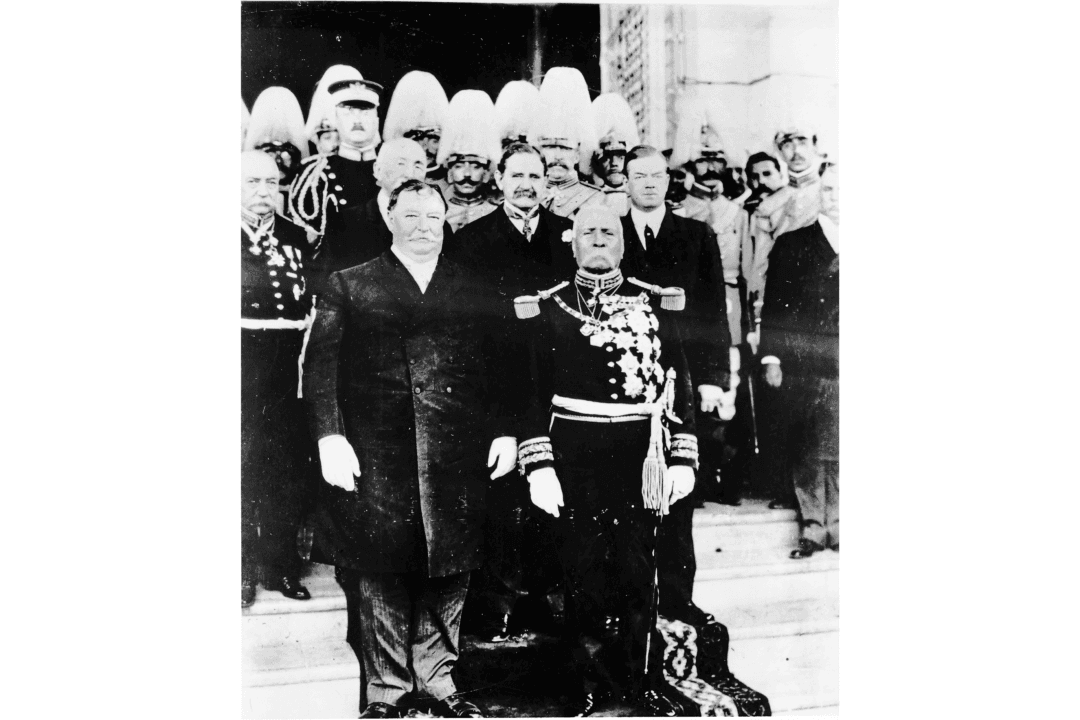

The executive experiences of President William Howard Taft and Mexican President Porfirio Díaz were strikingly different. Taft had yet to complete his first year in office, while Díaz was shoring up his third decade. Their rises to power were also strikingly different.

Díaz was a war hero in the fight against the French in 1867, as well as in his rebellion beginning in 1871 against what he proclaimed a fraudulent government. By 1876, his revolt succeeded, landing him in the country’s highest office. He served as president from 1876 until 1880, but returned in 1884 and remained until 1911.