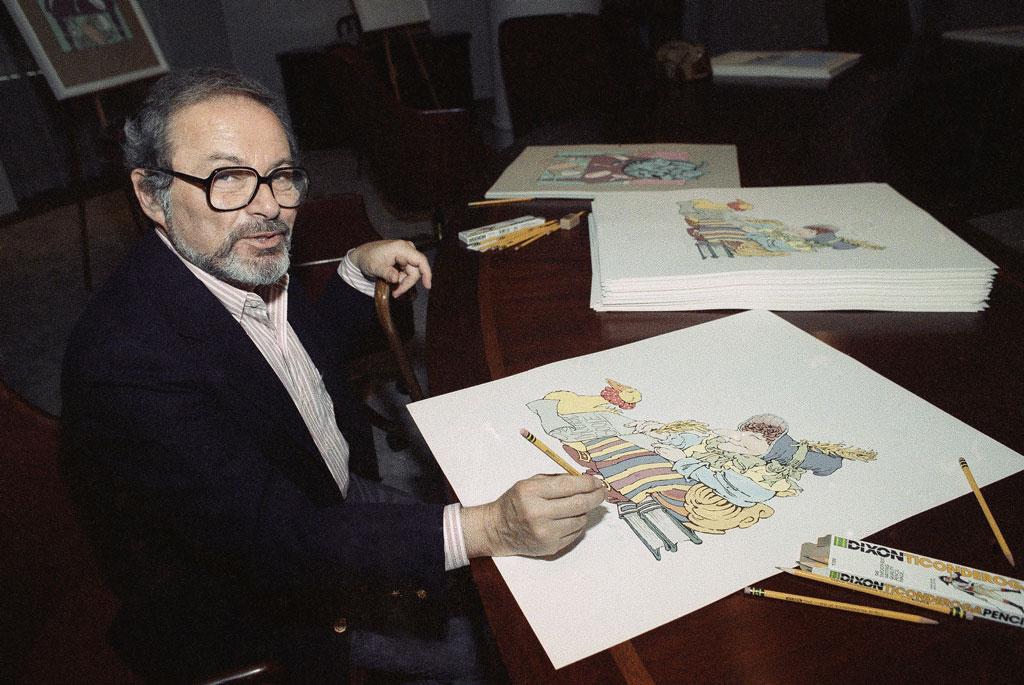

Maurice Sendak, author of “Where the Wild Things Are,” was an ardent defender of children’s literature, believing the works of Beatrix Potter to be equal to “the greatest English prose writers that have lived.”

One wonders therefore what he would have made of the rather unedifying row between the executors of his estate and the Rosenbach Museum and Library, to which he bequeathed his collection of rare books, including several volumes by Potter, on his death in 2012. His executors are refusing to hand them over, arguing that they are “merely” children’s books.

Thus the death of one of the great children’s writers of our generation has forced a court to seek a legal answer to a literary question, about which Sendak was surely never in doubt.

Alice in Lawyerland

My own research on Lewis Carroll’s protean and enduringly youthful heroine, Alice, has brought me into close contact with Carroll collectors whose houses are often filled from floor to ceiling with Alice editions and all manner of more or less related articles. While some have already made decisions about where to house their collections after their deaths, others are mulling over the possibilities.

In the light of the Sendak case, they would be well advised to pay close attention to the fine print and terminology of their bequests (not to mention the character of their executors). Are they leaving collections of children’s literature? Or simply of literature?

The literary merit of children’s books is regularly cast into doubt. What’s interesting and ironic about the wrangle over Sendak’s Potter books is that it brings into the frame both their cultural and their monetary value. It’s in the interests of the estate to hang on to them.

Big Business for Small People

Books for small people are indeed a very big business, one of the only parts of the global publishing industry to remain in relatively fine fettle, not only to survive but to flourish in recent years.

New works are being produced at a staggering rate and often to exceptionally high standards. At the same time, older works of a fairly substantial list of Victorian and Edwardian writers and illustrators, and all their associated items, are highly prized and sought after: just this week a Pooh drawing sold for a six-figure sum.

Classic children’s literature, such as Pooh and Potter, abounds on publishers’ lists and indeed often effectively finances new works. Interestingly, “classic” children’s literature tends to be the children’s books that adults often like, buy, and collect.

If the “literature” part of “children’s literature” is often called into question, the “children’s” part is no less problematic. Definitions of children’s literature inevitably crumble, made complicated by “crossover” books for adults and children—and by books which were for adults but flip into the children’s category (such as Gulliver’s Travels) and vice versa (arguably any of the children’s classics mentioned here).

This body of works, however designated, can of course become fossilized, reactionary, and dripping with twee Olde Worlde nostalgia. It’s often the stuff of endless, unimaginative re-editions. But it can also be cutting-edge and revolutionary—it can and does inspire new generations in new ways.

The ever-increasing avalanche of events and products scheduled for the 150th anniversary of the first publication of Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in 2015 makes this abundantly clear. Yes, there will be lots of (not always particularly innovative) new editions, but there will be others designed by Dame Vivienne Westwood, not to mention concerts and tattoo chains and exhibitions galore.

But Is It Art?

Classic children’s literature is, then, a particularly popular form of literature. For some, those two things still make uncomfortable bedfellows. Mass appeal is compounded by utilitarianism, which in the realm of creativity, has been regarded with withering disdain at best for the last century and a half. Asking whether children’s classics are on a par with literary classics, or a distinct subspecies, whether they are really literature, is akin to the question: “Is it really art?” And it plays on many of the same prejudices and sensitivities.

In the literary firmament, children’s literature—classic or otherwise—still tends to be seen as a minor constellation at best. But as with contemporary art, it will always depend on who is asking, when, and why.

Kiera Vaclavik is a senior lecturer in French and Comparative Literature at Queen Mary University of London. This article was originally published in The Conversation, www.theconversation.com