The celebrations of two fictional journeys coincide on one day, christening the date as both Dante Day and Tolkien Reading Day—March 25.

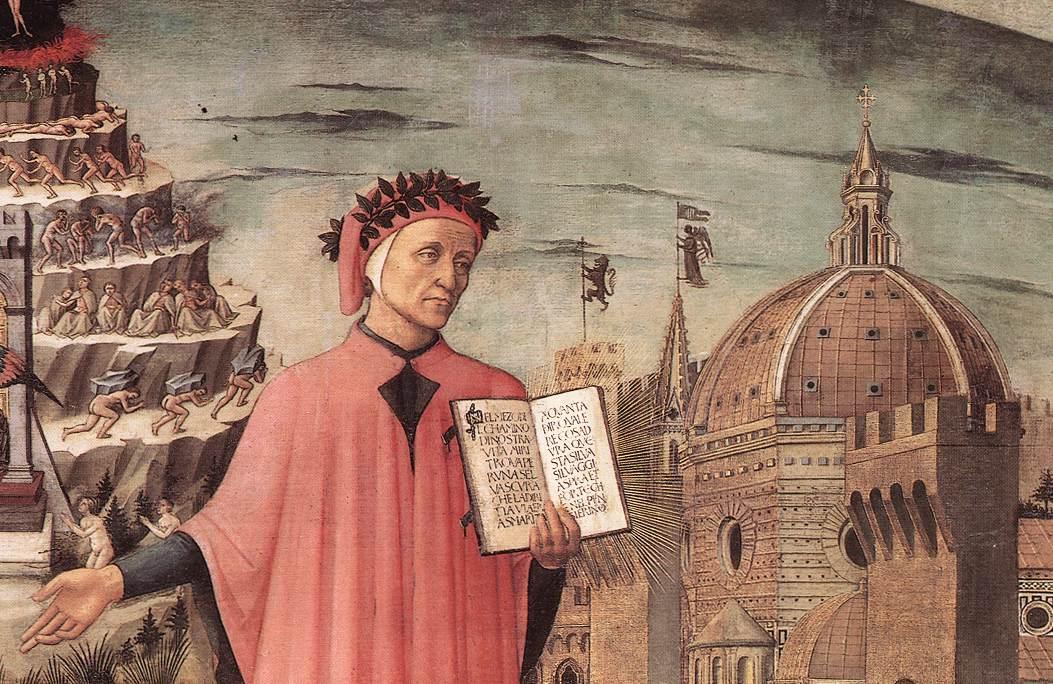

Despite more than 600 years between the lives of the two literary greats, this date is no coincidence. This is when Dante Alighieri the pilgrim begins his journey through hell in “The Divine Comedy,” and the ring of power is cast into Mount Doom in J.R.R. Tolkien’s “The Lord of the Rings.” The fact that this date figures into these two journeys makes sense considering the Christian beliefs of the two writers.