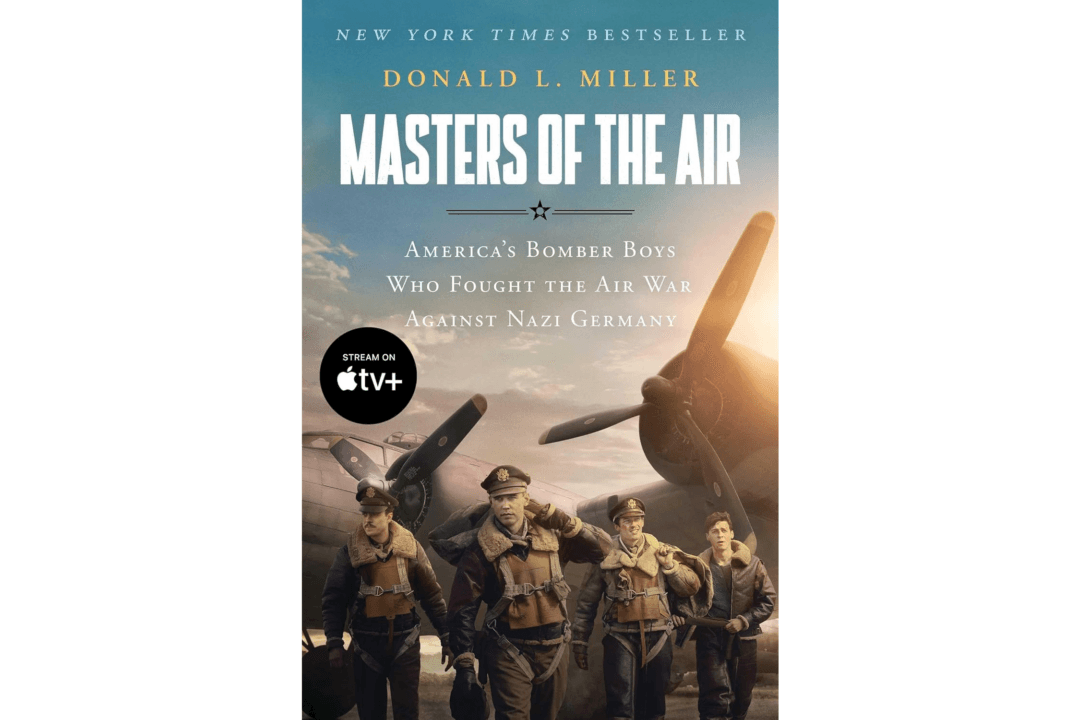

To land on a title for his book “Masters of the Air: America’s Bomber Boys Who Fought the Air War Against Nazi Germany,” author Donald L. Miller drew from Winston Churchill’s “Closing the Ring,” the fifth of a six-book World War II history series. Churchill wrote: “In the spring of 1944 … we were masters in the air.”

Every segment of military strategy and skill mattered during America’s involvement in the war, beginning after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941. Miller chose to zoom in on the bomber boys of the U.S. Eighth Air Force, which suffered more losses during the war than the U.S. Marine Corps but also inflicted catastrophic damage on the German war effort.