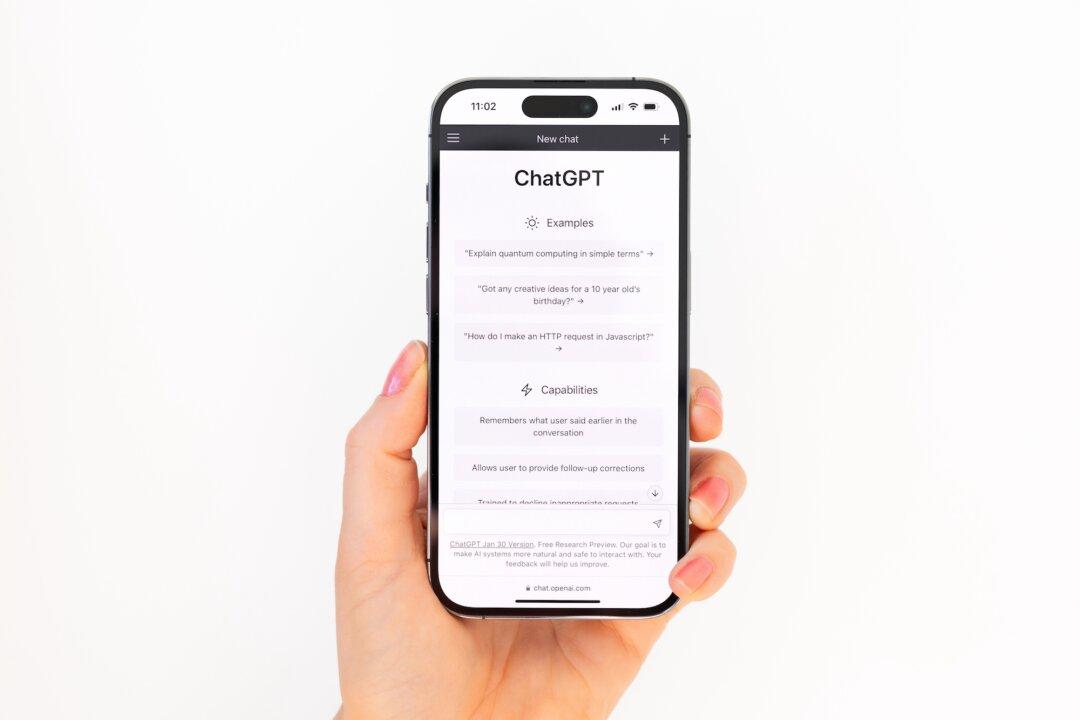

In their quest for the Holy Grail of teaching techniques, educators and parents alike have tried—and to their credit, are willing to try!—it all. Increasingly, it is technology that schools are turning to for breakthroughs, though often with a significant hit to the pocketbook. Only time will tell whether it provides the panacea many hope for.

What is becoming ever clearer, the longer I teach, is that it’s the simple things—done well—that work best. Often, it turns out that less is more.