To His Watch, When He Could Not Sleep

Edward, Lord Herbert of Cherbury

Uncessant Minutes, whilst you move you tell

The time that tells our life, which though it run

Never so fast or far, your new begun

Short steps shall overtake; for though life well

May scape his own Account, it shall not yours,

You are Death’s Auditors, that both divide

And sum what ere that life inspired endures

Past a beginning, and through you we bide

The doom of Fate, whose unrecalled Decree?

You date, bring, execute; making what’s new

Ill and good, old, for as we die in you,

You die in Time, Time in Eternity.

Look at your watch. What do you see? The second hand makes its calm stately round of the clock face. You are 60 seconds older. Sixty seconds closer to death. Sixty seconds closer to the mystery that defines existence.

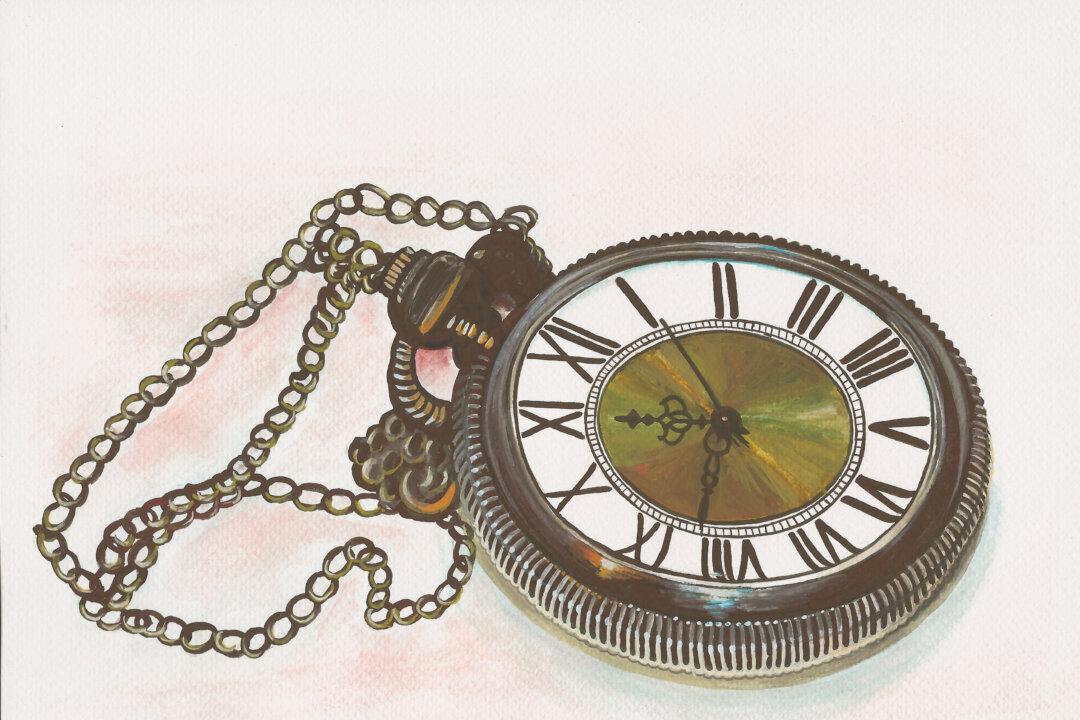

More than 300 years ago, Edward Herbert looked at his watch—presumably a pocket watch of the kind invented by Peter Henlein in 1510—and had a vision of creation. This is what we find in the terse, tense lines of this poem.

From the title, we know that Herbert cannot sleep. Immediately, we are drawn into the ambiguous small hours of nightmare and illumination. Herbert starts by addressing the “uncessant minutes,” as if the hands of the clock had become alive. They are like storytellers: telling the time that in turn tells our life.

The minutes’ short steps may complete their circle in a trice, decades before we die, but by endlessly renewing their revolution, these seconds will eventually “overtake” our three score years and 10. Our life may “scape” or “escape” our own “account,” meaning that while we may avoid understanding our condition—perhaps losing ourselves in the oblivion of business—we cannot avoid time’s judgment.

The minutes are “Death’s Auditors.” As the grim reaper’s phlegmatic accountants, they balance our credits and debits and reconcile them to zero. Whatever life inspires and endures falls under the remit of their cold, efficient, unwavering calculations.

We have no option but to “bide” our time, waiting patiently for the “doom of Fate,” as if we were all prisoners about to be marched out and shot. The “Decree” of doom is “unrecalled,” meaning it hasn’t been withdrawn.

At this point, the poem appears utterly pessimistic. Yet a sudden transformation occurs. As we watch all our hopes fading, as we watch ourselves die into the minutes and death dying into time, time itself dies into “eternity.”

The sound of the word “eternity” feels like a cold snap of water on our face. It comes as a brilliant relief, like the dawn breaking after Herbert’s sleepless night. Are we subject to happier laws than time? Look at your watch. It may hold the key.

Edward, Lord Herbert of Cherbury (1583–1648) was a British soldier, diplomat, historian, poet, and religious philosopher.

Christopher Nield is a poet living in London.