Few people realize that California’s Joshua Tree National Park sits between two deserts. To the east is the Colorado Desert and to the west is the Mojave Desert. With just a few feet in elevation change, from just under 3,000 feet to just over 3,000 feet, the wildlife, foliage, cacti, and rocks, are distinct. But the main similarity is that both landscapes receive only two to six inches of rain annually.

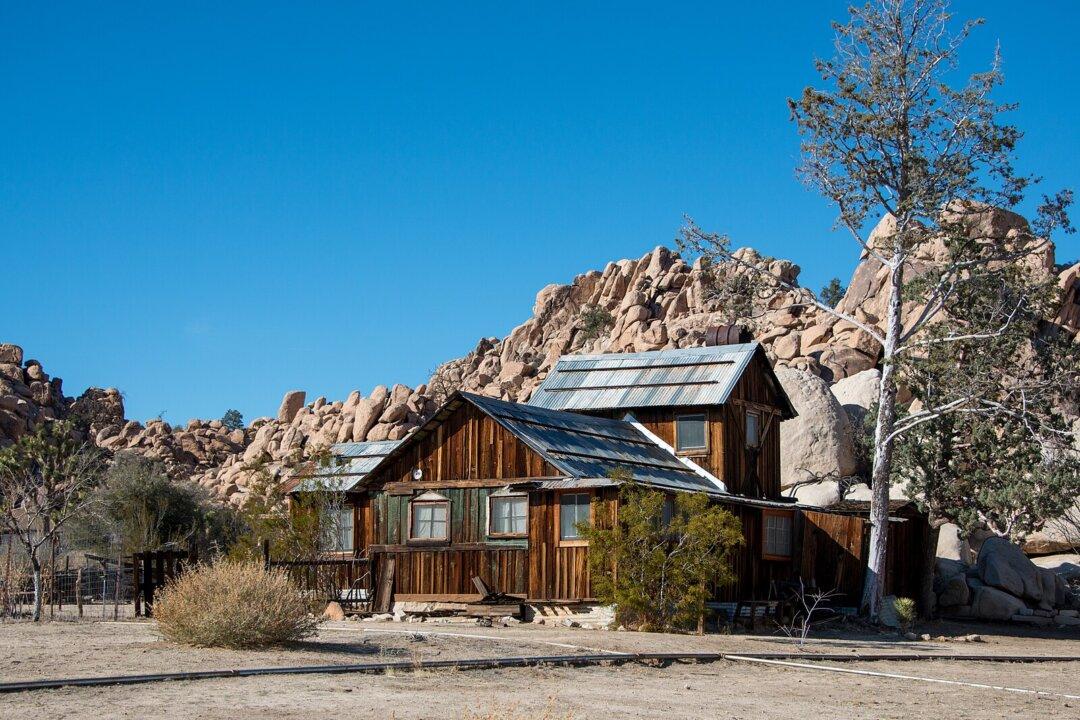

Few settlers sought to live in the region due to its dry, dusty climate and limited water. However, some men were drawn to the Mojave for its mining opportunities. In fact, copper, silver, lead, gold, zinc, and tungsten are elements and minerals mined in the region. Evidence of closed mines and rusted equipment still litter the landscape.