A sailing vessel from England called the North Carolina arrived off the coast of Maryland. Its destination was Baltimore, but try as it might, the ship could not reach the harbor. It was surrounded by ice, and it would be two months before it could free itself and unload its passengers.

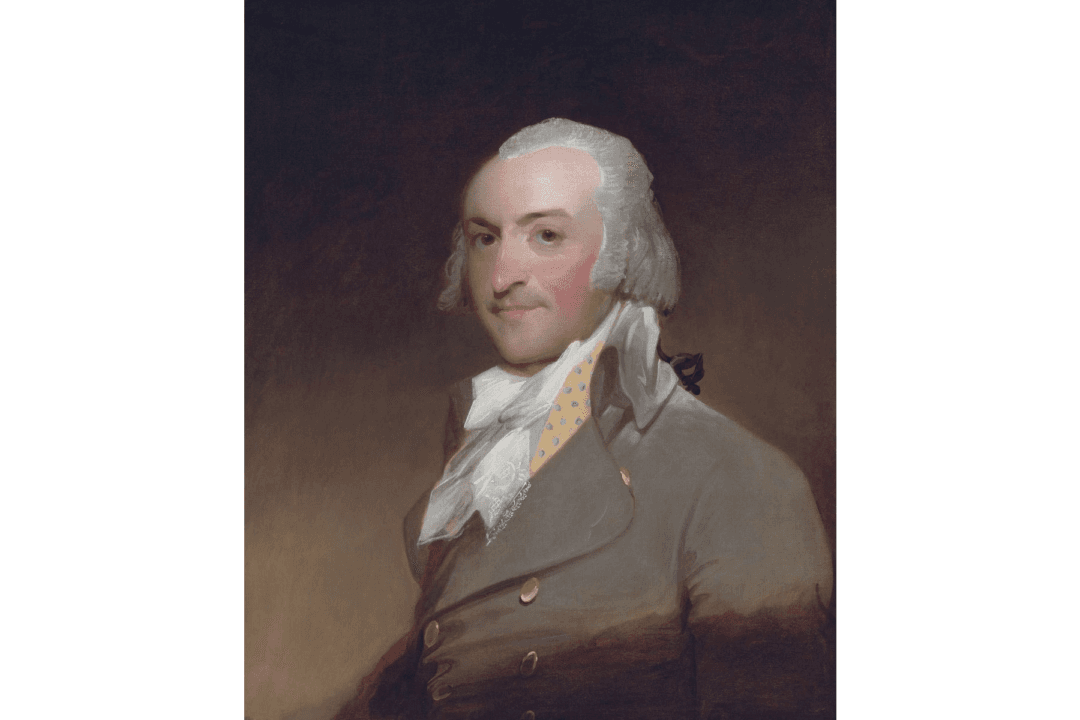

One of those passengers was the young German-born immigrant John Jacob Astor. He had boarded the vessel in November of 1783, approximately two months after the signing of the Treaty of Paris, which officially ended the war between America and Great Britain. It seemed a favorable time to depart for the New World. The only problem was the weather.