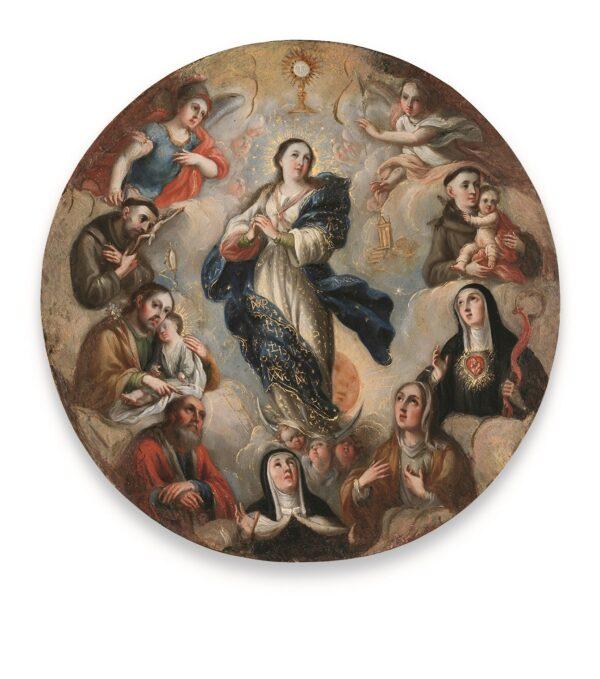

Oh heavens above! In a circular painting by 18th-century Mexican artist Antonio de Torres, a glorious Virgin hovers in heaven among a swirl of pastel clouds. As the Virgin looks up to God, she emanates divine light. A 12-starred halo crowns her head as she stands on a crescent moon, with a jolly sun peeking out from behind her; each of these motifs refers to Revelations 12:1 in the Bible. Saints surround her, with some gazing adoringly up at her, and others gazing out of the painting to encourage our faith.

A nun’s badge with the Immaculate Conception and saints, Mexico, circa 1720, attributed to Antonio de Torres. Oil on copper; diameter: 7 inches. Purchased with funds provided by the Bernard and Edith Lewin Collection of Mexican Art Deaccession Fund, Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Public Domain