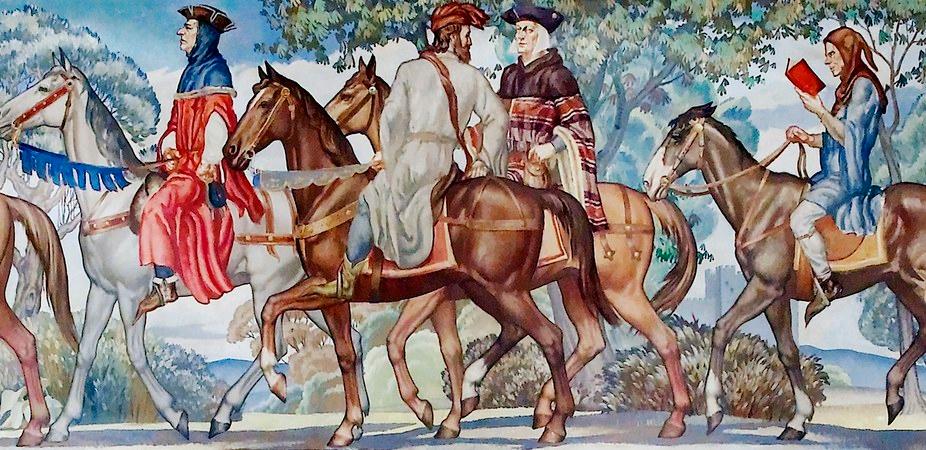

On New Year’s Eve, four of my five siblings, their spouses, and I gathered to ring in 2020. At one point, our conversation turned to long-ago college classes, and my sister, who is a wife, mother, grandmother, and a banker, suddenly said: “Whan that Aprill, with his shoures soote, The droghte of March hath perced to the roote.”

Whan that Aprill, with his shoures soote The droghte of March hath perced to the roote And bathed every veyne in swich licour, Of which vertu engendred is the flour; Whan Zephirus eke with his sweete breeth Inspired hath in every holt and heeth The tendre croppes, and the yonge sonne Hath in the Ram his halfe cours y-ronne, And smale foweles maken melodye, That slepen al the nyght with open eye — So priketh hem Nature in hir corages; Than longen folk to goon on pilgrymages And palmeres for to seken straunge strondes To ferne halwes kouthe in sondry londes; And specially, from every shires ende Of Engelond, to Caunterbury they wende, The holy blisful martir for to seke That hem hath holpen, whan that they were seeke.