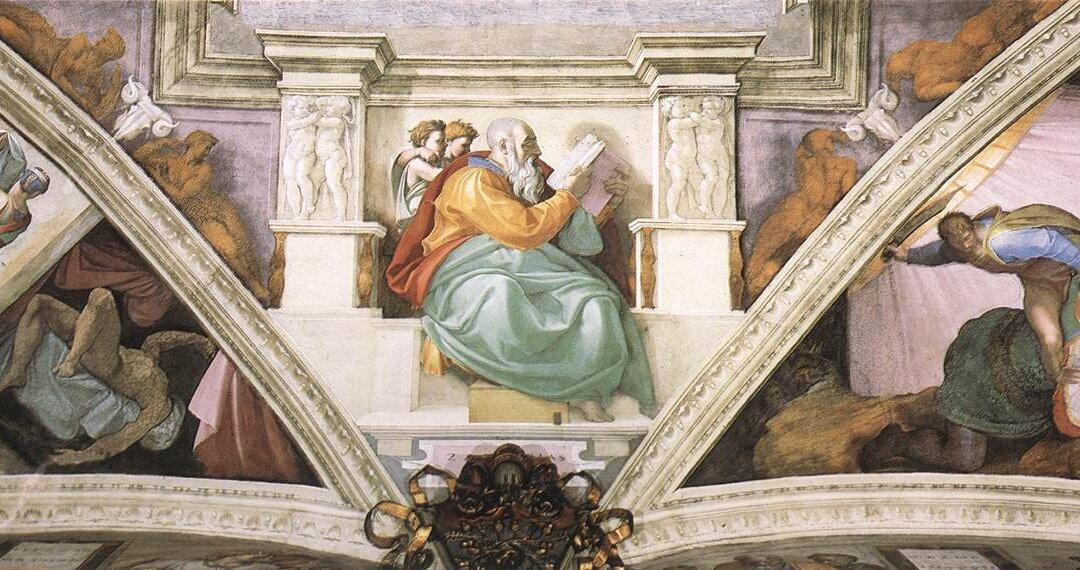

For almost four years it was a common sight on Vatican Hill. Between eight and a dozen men at their various tasks: Mixing plaster, using pick-axes to give a ceiling the rough surface which helped plaster stick, applying plaster and painting it.

Does that sound like an ordinary construction job? It’s actually how one of history’s greatest artistic masterpieces was created—Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling.