Long before the “Night at the Museum” movie franchise, The Metropolitan Museum of Art made a dynamic Hollywoodesque “knight at the museum” film entitled “A Visit to the Armor Galleries.” It was released in 1924 as part of a program to make their spectacular arms and armor collection come alive for the public’s education. Enchanting scenes include a suit of medieval armor leaving its glass case to answer visitors’ questions, a knight in full armor on horseback galloping through Central Park with the Belvedere Castle folly in the background, and curators attiring themselves, from helmet to sabaton, for a swordfight and joust. There is record of the Hollywood actor Douglas Fairbanks Sr., famous for silent swashbuckler films, being impressed by the film.

Lauder’s Collection

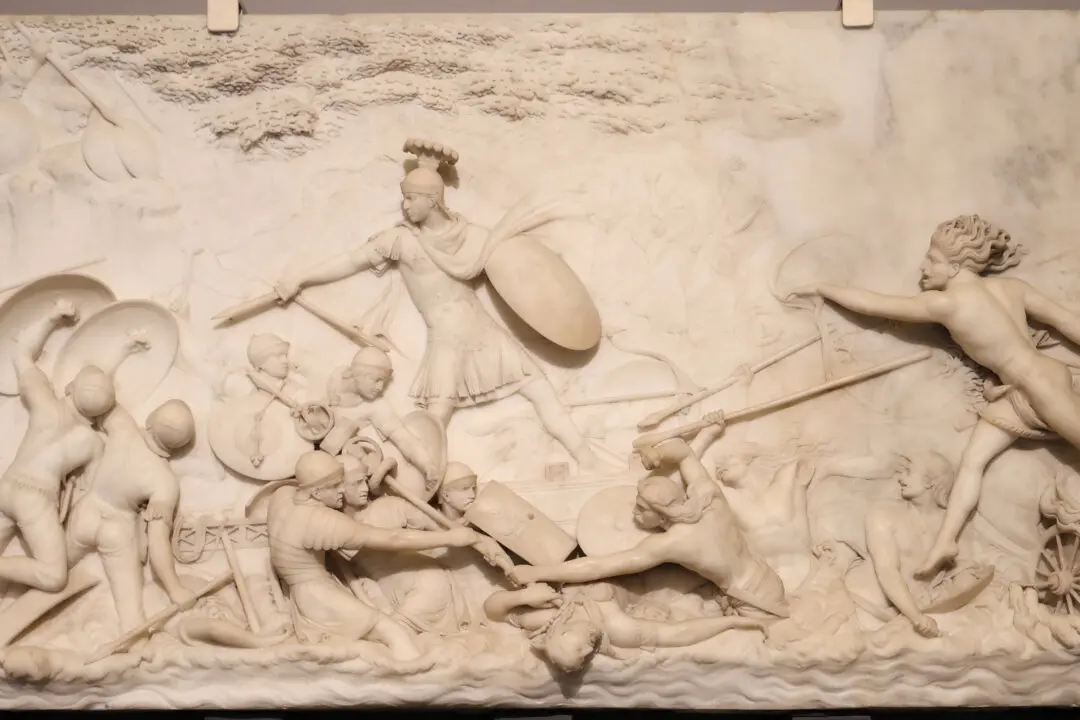

Arms and Armor Department at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. Diego Grandi/Shutterstock