In a quiet room at the end of a hallway in the Ottawa Art Gallery is a small exhibition by Canadian photographer Rémi Thériault, perhaps 12 large pigment prints in all.

They are photographs of summer landscapes—green fields, forest glades, a few village streets. For the most part, there is nothing remarkable about any of the scenes Thériault photographed in 2011 unless the viewer knows these places were once World War I battlefields.

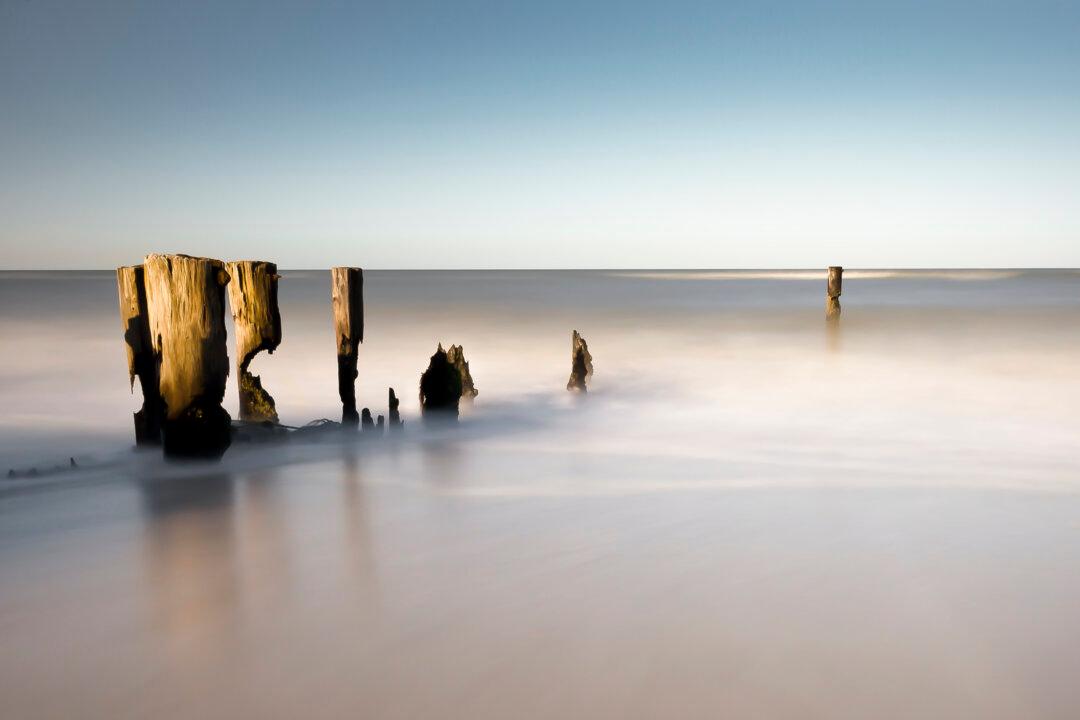

On one wall are two paired views of a flat land—“Loos-en-Gohelle 1, 2,”—each framed in white wood. Looking at them side by side is like looking through the windows of a beach cottage onto a seashore stretching far away. In the foreground we see barren earth marked with vehicle tracks and tractor treads. At the horizon is a long, low, white structure. No way to know what it is. The gallery’s picture caption supplies no information other than a site name, misspelled. A war historian might recognize the site. If so, the Loos Memorial in France commemorating the deaths of nearly 21,000 British soldiers may be nearby.

“Flanders Field 2” presents a view looking down a hill. At the bottom is a crumbling bunker cut into the hillside, covered with dirt. Trees have grown thick around it. The foreground is blurred. Maybe that is our hiding place today. Nothing neat or tidy here.

“Vimy Forest, historical 2” is a scene of soft little mounds of spring grass strewn with daisies, dandelions, and Queen Anne’s lace tumbled one upon the other. Their curves are repeated in the foliage of dark trees surrounding—as above, so below—and beyond all that a grey metal sky. If these are graves, they are not marked.

The mound we see in “Vimy Forest, private 1,” however, is more secluded. It is buried in a heavy overgrowth of vegetation. Trees are crushed in and around the mound. Whatever secrets it holds will stay hidden in this dense, dark glade.

A corn field with its maturing crop was photographed against a grey sky. Titled “Courcelette 1,” the scene is quite ordinary both in composition and content. Only its title indicates it is something other than any farmer’s field anywhere. Courcelette was the site of a WWI battle.

The photograph titled “Beaumont-Hamel 1” is more informative. At a distance, we see a row of tourists filing into rebuilt trenches. Sheep graze in the meadows nearby. The tourists, all neatly dressed in suits and coats, appear to be grey- and silver-haired travellers. The war fought here took place 100 years ago, so it was not they who fought it; it was others, not unlike them, who dug the trenches then.

There were many battlefields in WWI. The ground was torn and littered with broken bodies and the debris of battle from Africa to Bulgaria, Turkey to France, from Belgium, Germany, and Serbia to Mesopotamia, Palestine, and everywhere in between. The armies of those battles were sent to their deaths by most of Europe, including the nations of the British Commonwealth, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, plus Japan, the United States, and Russia.

The battlefields Thériault chose to study and photograph are all sites in northern France where Canadian and British armies fought along the Western Front in the Somme Offensive from 1916-1918.

However, the gallery does not provide sufficient location information for the photographs. Although the exhibition is titled, “Front,” there is no indication the photographs were taken of old battle sites in northern France. Not every visitor will recognize the titles as names referring to historic events of the last century.

“Front: Photographs by Rémi Thériault” will be on display at the Ottawa Art Gallery until June 8. The exhibit is curated by Ola Wlusek.

Maureen Korp, PhD is an independent scholar, curator, and writer who lives in Ottawa. Author of many publications, she has lectured in Asia, Europe, and North America on the histories of art and religions. Email: [email protected]