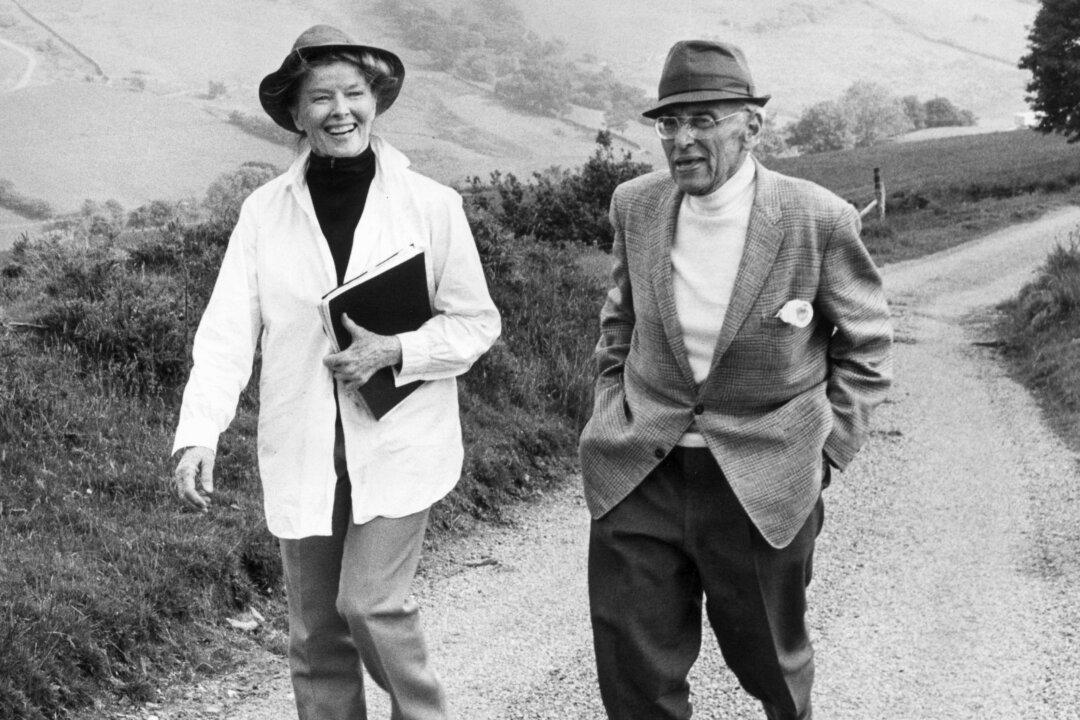

Katharine Hepburn wasn’t your typical Hollywood actress. She wasn’t a glamour girl, nor was she a clothes horse. She didn’t fit the leading lady role, since she neither was a classic beauty nor a traditionally feminine woman. Tall and slender with angular features and a strong personality which shone through on the screen, Hepburn wasn’t suited to play the hero’s stereotypical love interest. She was, however, an excellent actress, but filmmakers often misunderstood her.

Director George Cukor appreciated Katharine Hepburn’s talent. He directed her first screen test and, although other studio executives were unimpressed, the naturalness with which she picked up a glass struck him. He used simple gestures like that as powerful moments in all the films he directed with her.