German musician Jörg Widmann says that for him, everything began with the clarinet. He started playing the clarinet at age 7; shortly after, he discovered the piano, along with the impulse and ability to write music. Surrounded by peers who too were playing instruments, he had ample opportunity to hear his music come alive.

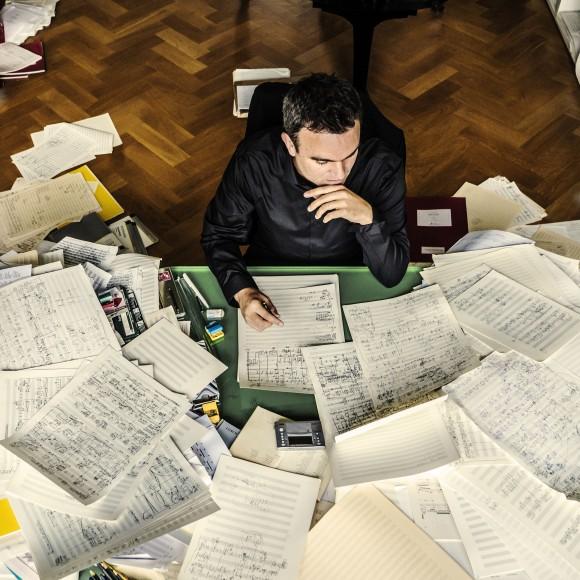

“I just finished a new oratorio for a new concert hall in Hamburg, which will premiere [this] week, and I’m quite exhausted. But there is a new piece in my mind. ... It’s already starting,” said Widmann. “It’s not a question about how I feel about it, I have no choice—it’s an obsession in the most wonderful sense.”