Jeremy Adams, a self-proclaimed “unapologetic romantic about the United States,” has been teaching high school civics in California for nearly 25 years. A decade ago, he was named the Daughters of the American Revolution California Teacher of the Year. He was also a finalist for the Carlston Family Foundation Outstanding Teachers of America Award.

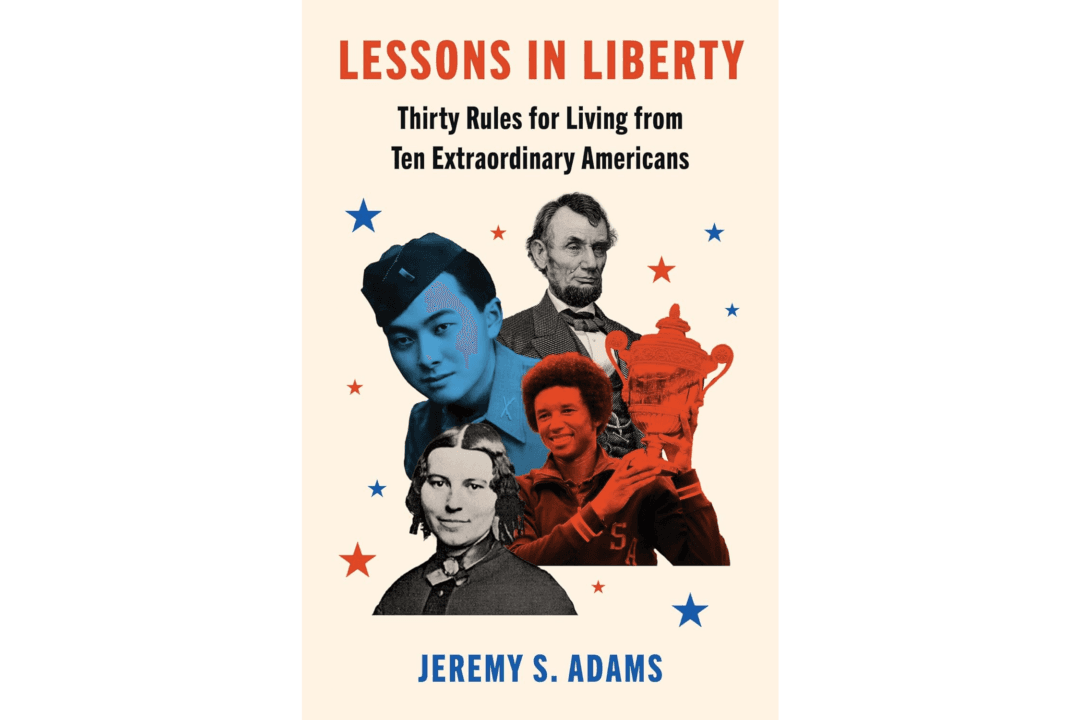

Adams has long been in the educational trenches, helping students understand what it means to be an American, and the heritage and responsibility that comes with it. Living in California, he has also witnessed the detrimental impact of educational agendas that focus on American history’s negative elements. As Adams suggests in his new book, “Lessons in Liberty: Thirty Rules for Living from Ten Extraordinary Americans,” that type of education does more harm than good.