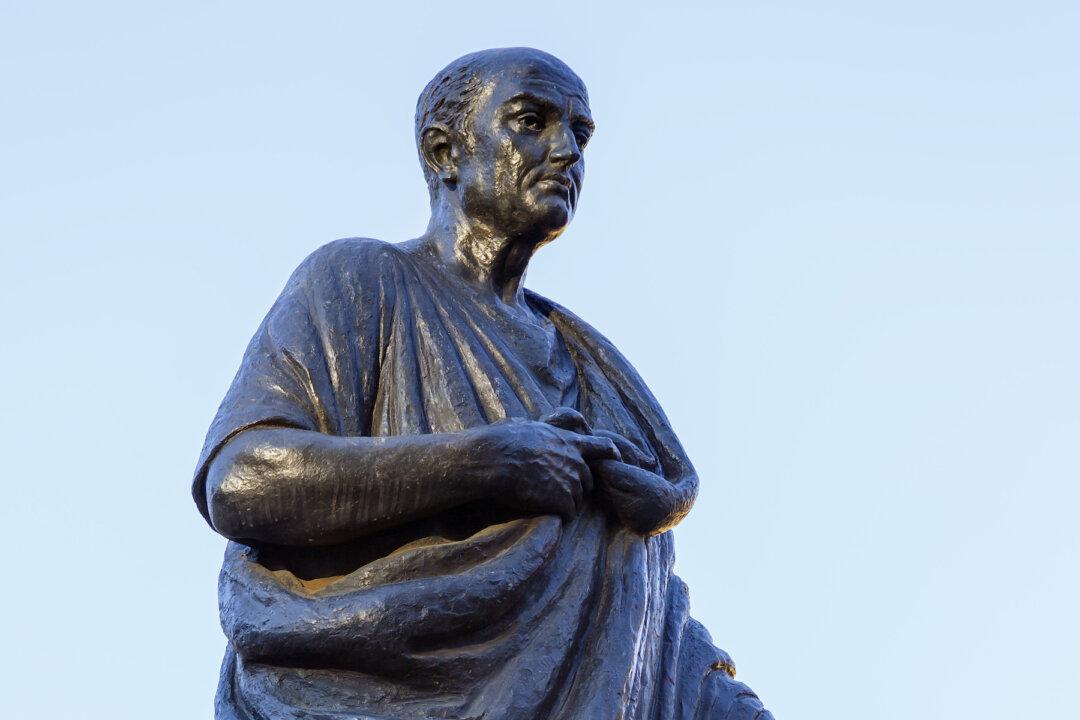

Thomas Jefferson died with a volume of Seneca’s works on his reading stand. George Washington owned a treasured copy of the Roman’s philosophy “Morals by Way of Abstract,” which he consulted regularly. Indeed, Seneca inspired many of the Founding Fathers, who credited him and his fellow Stoics, with ideas that informed the Declaration of Independence.

Philosopher Ryan Holiday’s “The Obstacle Is the Way: The Timeless Art of Turning Trials into Triumph“ showed the world that Seneca’s influence continues in the 21st century. The book, which borrows from the Stoic’s beliefs on facing challenges with poise, has sold over a million copies since publication, becoming a favorite of top-notch athletes and a plethora of accomplished people. Seneca has even appeared in a recent movie that marks his first televised biography. The film portrays the philosopher’s career as an advisor to the impetuous Emperor Nero, putting a face on the oft-cited but mysterious man.