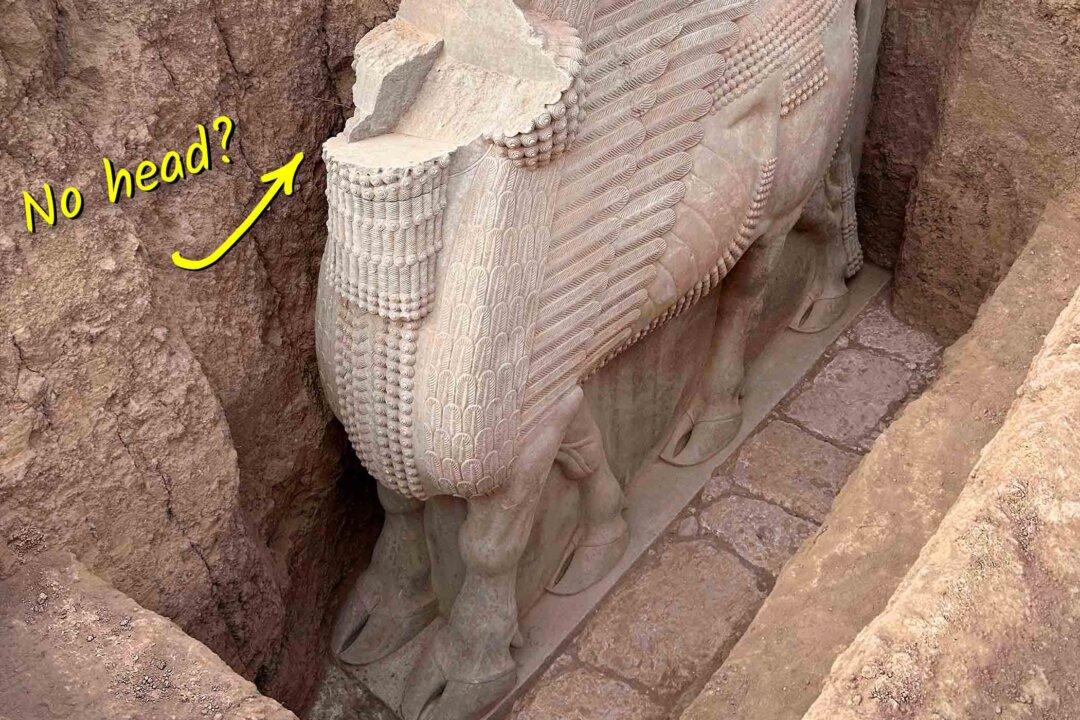

The guardian was caught in limbo, standing beneath and above the sand, and between warring factions in the desert for several decades. The ancient statue had seen better days—this one was headless.

“The attention to detail is unbelievable,” said Pascal Butterlin, a professor of Middle East archaeology at the University of Paris, working at an excavation near Khorsabad.