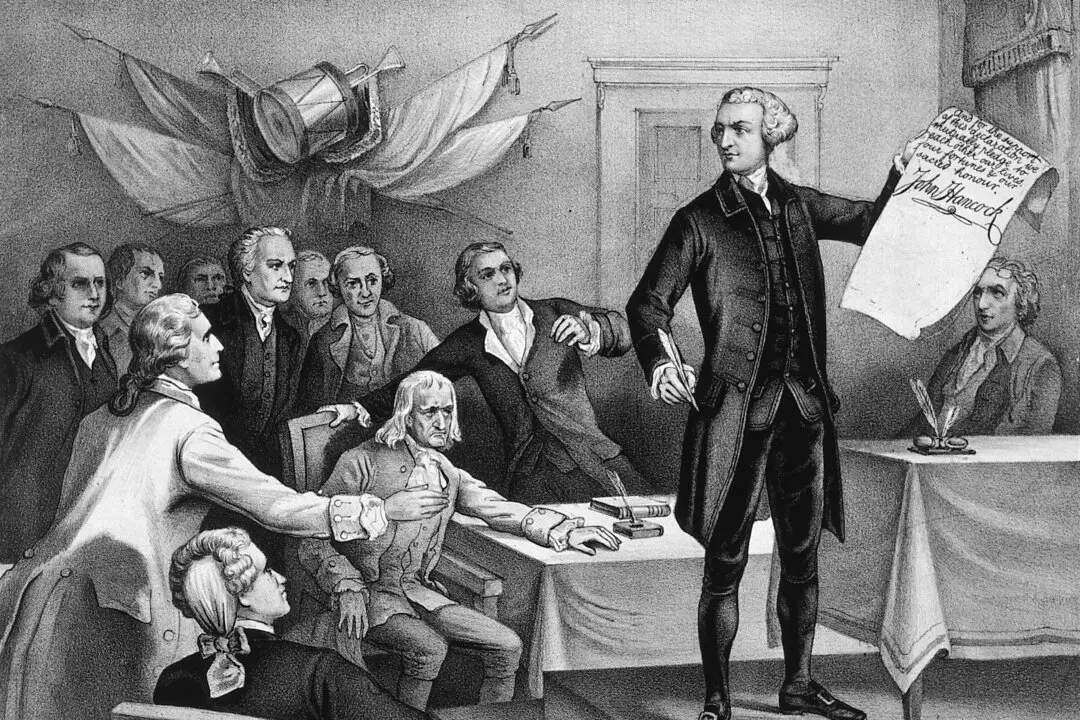

A cold civil war permeated Britain’s American colonies in the summer of 1774, chilling the Patriots (Whigs), Loyalists (Tories), and the Royal Authority. For the previous decade, these disturbances primarily originated from Britain’s Parliament. Its members claimed to have the authority to rule all British subjects throughout the world.

Such claims divided friends and families who had chosen opposing sides and bred resentment toward politicians writing the laws and toward officials enforcing them. Numerous protests spilled over into violence, alarming officials on both sides of the Atlantic.