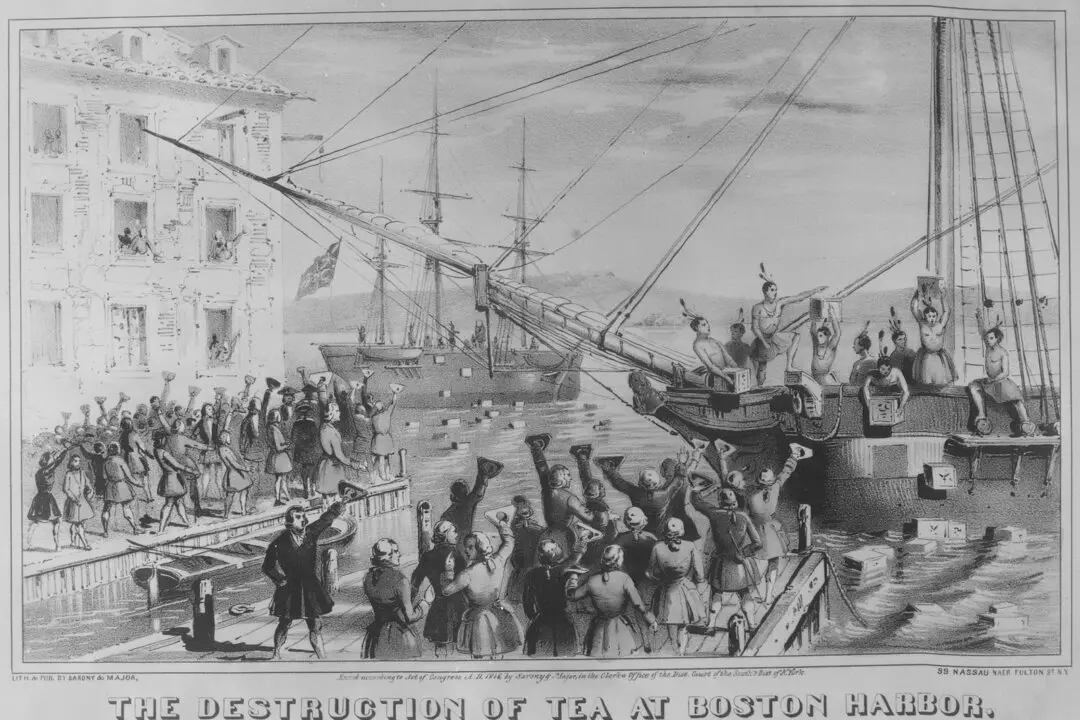

As the tea in the Boston Harbor cleared, reaction poured in.

“This is the most magnificent Movement of all. There is a Dignity, a Majesty, a Sublimity in this last Effort of the Patriots, that I greatly admire. ... This Destruction of the Tea is so bold, so daring, so firm, intrepid, and inflexible, and it must have so important Consequences, and so lasting, that I cannot but consider it as an Epocha in History,” said John Adams.