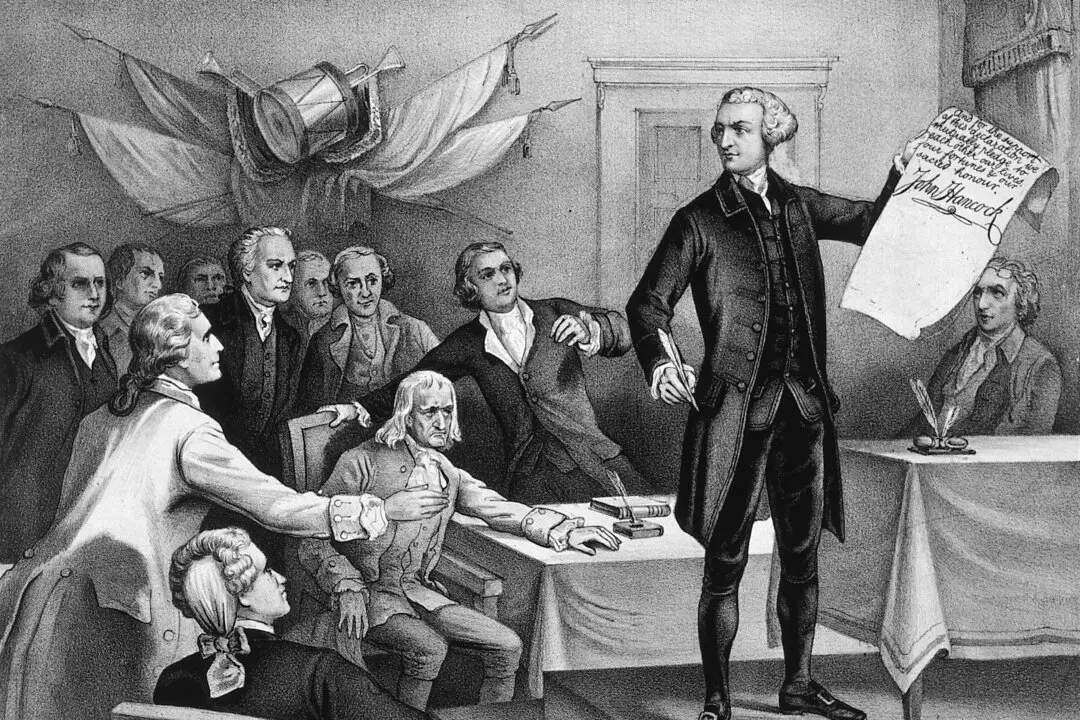

As discussed in Part 1 of this series, harrowing stories from Boston of mass destruction and casualties inflicted by British artillery units continued pouring into Philadelphia. Capturing the tension in Carpenters’ Hall, Silas Dean wrote to his wife, “An express from N. York confirming the acct. of a rupture at Boston. All is in confusion. I cannot say that all faces gather paleness, but they all gather indignation, and every tongue pronounces revenge.”

On Monday, Sept. 5, efforts to open the First Continental Congress with a Christian prayer faltered due to the doctrinal disputes that existed since the Reformation. By late Tuesday, however, news of the British assault on a sister colony united the delegates, prompting them to set aside their petty differences. They agreed to have Rev. Jacob Duché, the Anglican minister of Philadelphia’s Christ Church, deliver the opening prayer on Wednesday morning.