On a tiny island on the world’s second-largest freshwater lake two nations wage Africa’s “smallest war.”

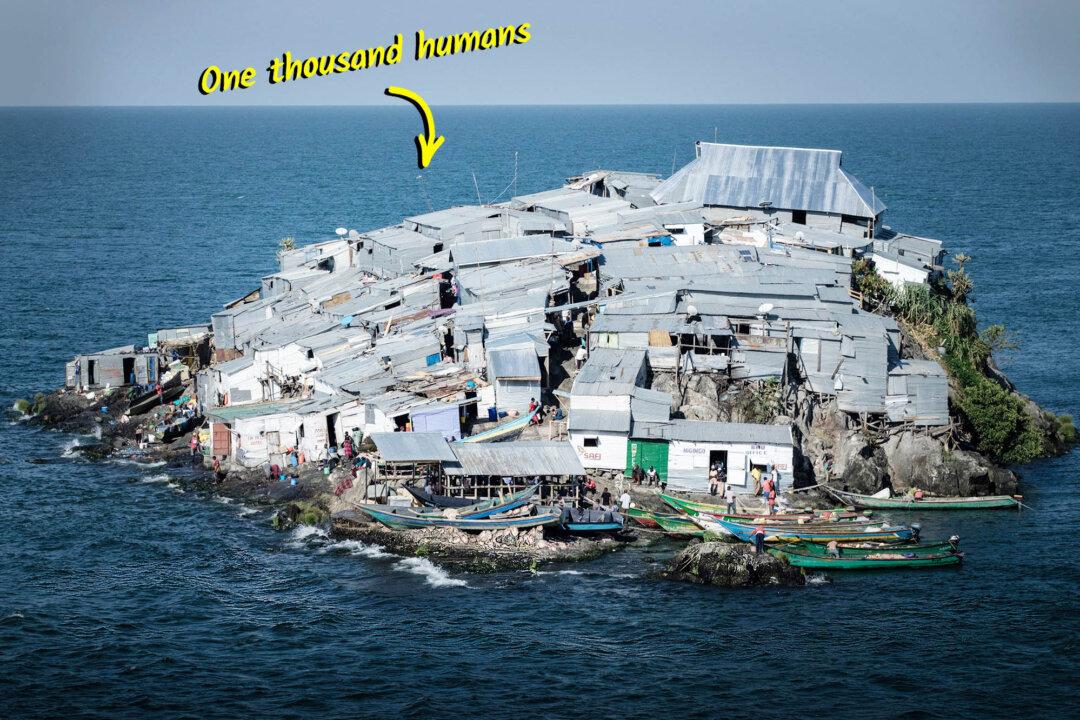

An iron-clad tortoise of rock and sheet metal juts from Lake Victoria, christened after Britain’s late queen, surrounded by over 23,000 square miles of water. Here a thronging mix of nationalities mingles—despite territorial disputes, competition over fishing, and myriad viewpoints—all in relative harmony on an island less than half the size of a football field.