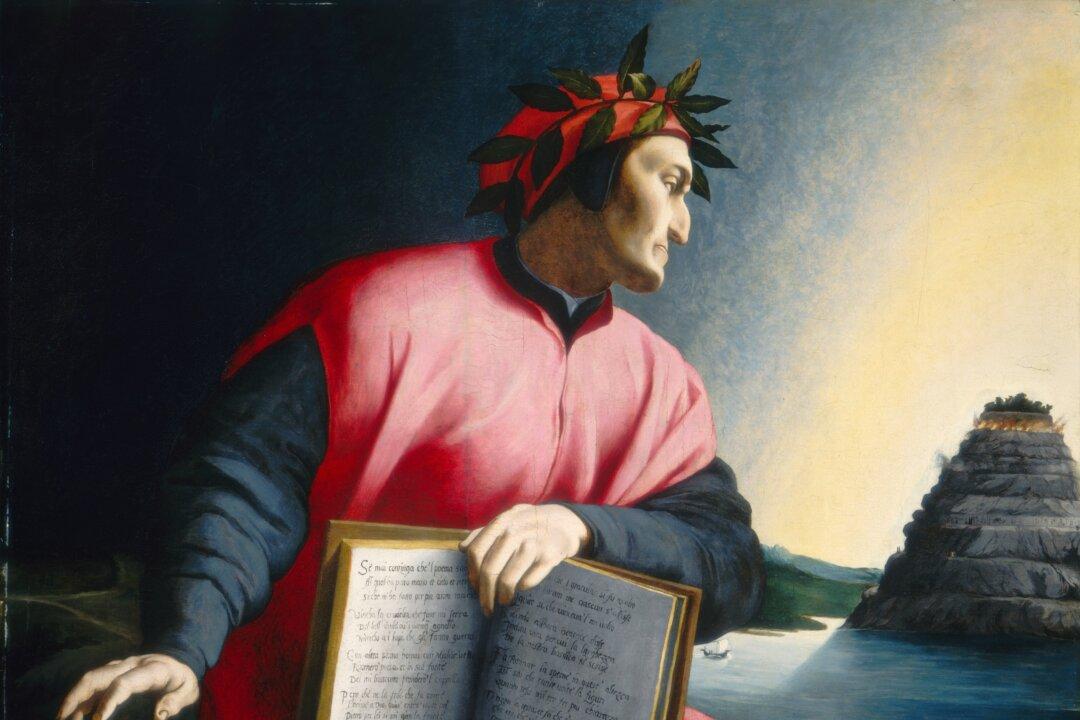

Gratifyingly, as we have now passed (Sept. 13 and 14) the anniversary of the death of Dante Alighieri 700 years ago (1321), there has been a massive upsurge in interest and promotion of his work, especially of “The Divine Comedy,” arguably the world’s greatest poem.

This is really good news. In the UK, for example, we find the artist Mark Burden publishing a series of fascinating art pieces representing each of the 34 cantos of Dante’s “Inferno.” Burden’s short YouTube video is well worth a watch.