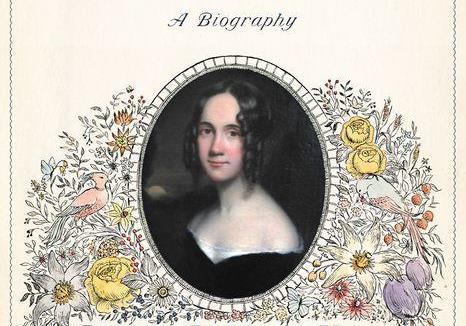

It’s a name that many, if not most, people are unfamiliar with—unless they remember the name of the author who wrote the nursery rhyme “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” I was unfamiliar with Sarah Josepha Hale until reading this book, but upon completing it, I feel a sense of regret knowing that she has been all but forgotten. Melanie Kirkpatrick’s new book “Lady Editor: Sarah Josepha Hale and the Making of the Modern American Woman” looks to change that, at least to some degree.

The story of Hale is one of perseverance, courage, and talent, girded by wisdom. Kirkpatrick takes the reader through Hale’s young life that begins in 1788 (died, 1879), the year before the Constitution was ratified. The following year, President George Washington made his Thanksgiving proclamation. This holiday would play a pivotal role in Hale’s life.