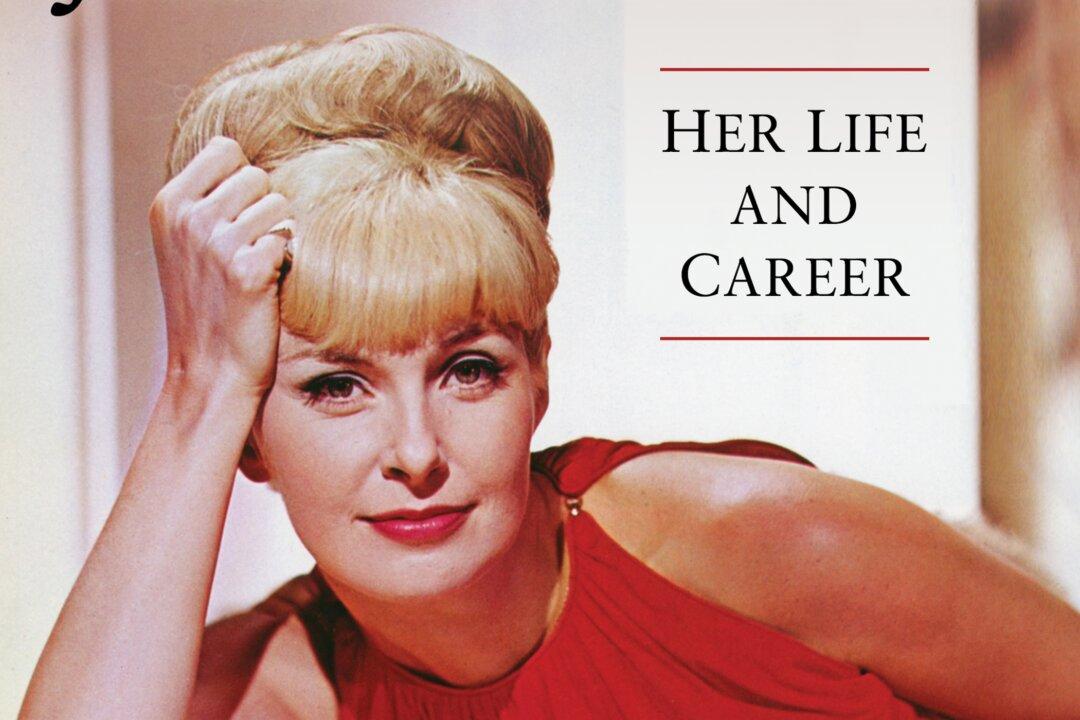

For better or worse, actress Joanne Woodward (born Feb. 27, 1930) will always be linked with her late husband, Paul Newman. It’s an issue brought up time and again in Peter Shelley’s biography “Joanne Woodward: Her Life and Career,” which looks at the couple’s life together, interwoven with explorations of Woodward’s professional career. Shelley notes that while there have been multiple biographies of Newman and of the two as a couple, this is the first work focusing specifically on Woodward.

While Shelley has certainly done his research on Woodward’s career, including a detailed list of the actress’s film, theater, and television credits, his efforts are not always so clear when it comes to Woodward as a person. All of the book’s information come from sources of the time; that is, newspaper articles and television interviews, without any firsthand comments—such as from her children or longtime friends—to better put her life in perspective.