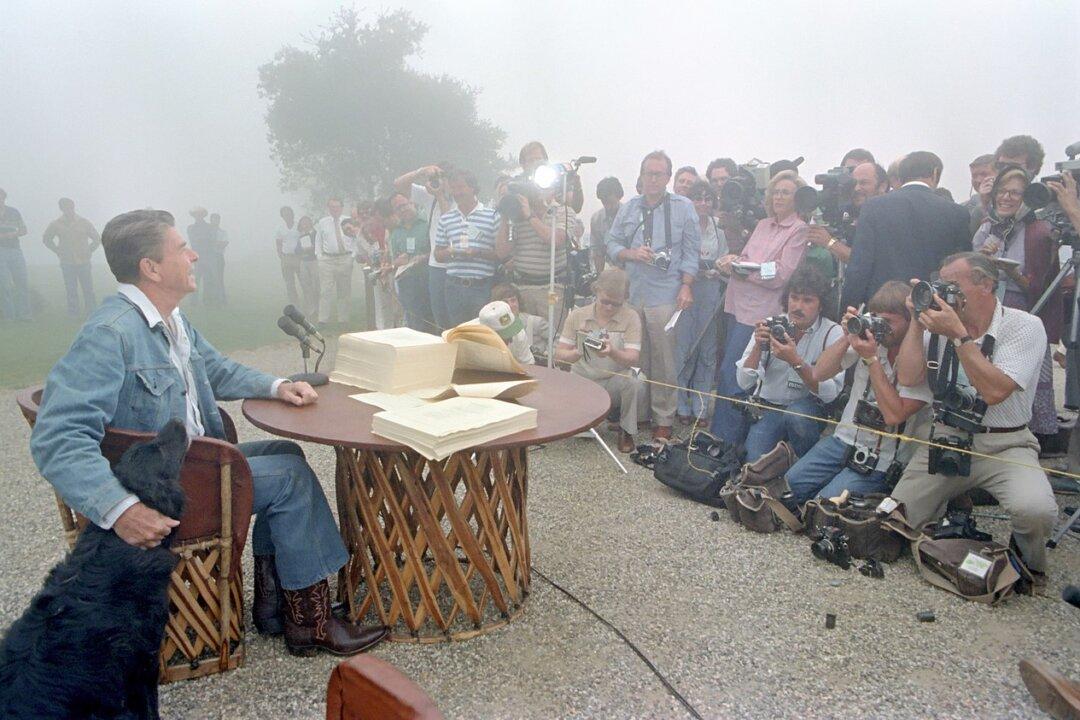

Across the educational landscape, from K–12 on through the universities, the liberal arts and history, in particular, are being downplayed and discouraged. In some cases, this is an effort to steer young people to math and science studies that are likely to lead to solid careers.

But others oppose the way that traditional U.S. history and Western civilization have been taught.