The Revelation of Death

A Reading of an Extract From Sir Edwin Arnold’s ‘The Light of Asia’

What is our response to death? Not in the abstract but in the horribly, humiliatingly particular? What is our reaction when we see a body broken into pieces, burned, or tossed into the ground, with apparently no trace of its former humanity, no trace of soul?

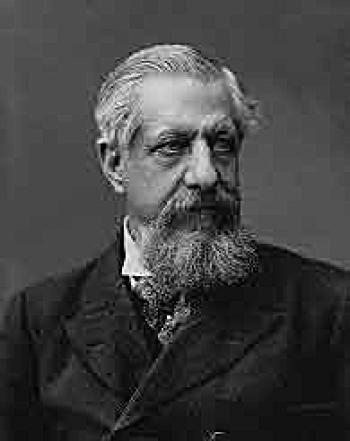

Sir Edwin Arnold. Public Domain

|Updated: